The parallel universe – the land of the jinns

Throughout human history all cultures have been captivated by a belief in invisible parallel worlds inhabited by small beings. We can call them fairies, elves, gnomes, leprechauns, woodatji or jinns. They all serve the same function – to control behaviour and to give a rational explanation of the “unexplainable.” The Sasak villagers of Western Lombok dwell beside jinns not because they see them but because they believe in them.

My Sasak assistant Bado had arranged for me to meet a traditional belian (shaman) by the name of Amak Alam. He described him to me as an “old style” belian who still practised the folk Islamic religious tradition known as Waktu-telu meaning to pray three times a day instead of the orthodox five times a day.

Bado’s opinion of this elderly belian was ambivalent displaying his feelings of fear (geleget) and disapproval (gnolok). He described Amak Alam as “primitive” and explained that his religion was regarded as agama belum – ‘one that has not yet arrived at the true faith Islam.’ Bado ridiculed the source of his ilmu (knowledge) by stressing that it did not come from a pious Tuan Guru (a highly respected religious teacher) but from a high-ranking jinn sorcerer by the name of Dewa Kabut. I got the feeling that Bado was not looking forward to our meeting with Amak Alam.

We walked for a considerable distance from the end of the road along steep narrow dykes of neat, newly planted rice paddies towards a picturesque river valley where a few remote dwellings were located. I could sense Bado’s anxiety intensify as we climbed down through an area of dense vegetation, that I casually referred to as “jungle” but was abruptly corrected by Bado who said it was someone’s “garden” not a jungle. He looked around nervously and said to me in a hushed voice that we were most probably walking through the village of some primitive jinn.

‘You must be very careful in places like this Mr Ken, because the jinns that inhabit these remote places are very dangerous. They are not Moslems like us but are kapir (heathens). We call them ‘bakeq’ (dangerous infidel jinns).’

I noticed Bado beginning to perspire as he looked around with nervous anticipation and then he softly murmured:

‘Pak Jumali told me that these jinns still possess the ilmu (knowledge) and jampi (spells) of the ‘toker goneng’ (the ancestors). They have celaka (malicious magic) so we must not anger them.’

I remember waiting to interview Amak Alam and as usual my assistant Bado had wandered off and left me alone with the old man whose only language was Sasak. I could see Bado in the distance gossiping with some locals so I called out to him loudly: ‘Bado, come over here I need you to translate for me.’ I was about to repeat myself, when Amak Alam glared at me intensely with displeasure. I instantly felt that I had offended the old man by breaking some adat custom or code of etiquette. I apologised to him in Indonesian but he took no notice. When Bado returned I asked him if I had offended the old man in some way? By this time Amak Alam was scolding Bado in a grandfatherly way. Bado stood nodding his head in agreement with every word the old man uttered and when he had finished Bado said:

‘I was very wrong to leave you, Mr Ken, I must take better care of you next time. It is not safe out here, for you do not understand the perils of this place.’

Why, I exclaimed, beginning once more to feel the frustration of not being able to speak Sasak. ‘Well’ Bado hesitated, as if trying to find the right words:

‘You see Mr Ken, you must never call a person’s name when you are in jinn country. There are many jinns who live in this area.‘

He pointed to what I had mistaken as “jungle” and then resumed talking.

‘If you call a person’s name, it may be a jinn child who has the same name as that person you are calling who comes to you. Jinns are invisible and if a child obeys your command and you accidentally hurt it, the mother will be very angry and may attack you, or even worse, get her brothers or husbands to assault you. Jinns are quickly angered especially when it comes to protecting their children.’

Bado hesitated and then spoke with great insight:

‘Jinn parents protect their children, and in return when they are old, the children protect them. It is the same way as we Sasaks.’

When I returned to Senggigi in Western Lombok the following day, I visited Pak Bahar in a village close by. Pak Bahar is a well known and respected belian who is a confessed Muslim and an expert in the realm of all things mysterious. When I asked him about the dangers of name-calling, he said in an authoritative voice that long ago when a person died, the ground where they were interred was levelled soon after in order to conceal signs of a human burial. The reason was to prevent a jinn by the same name from being interred in the same grave. When he had finished his explanation, he recited a Bismillah (an invocation of mercy to Allah) under his breath.

Bado had advised me soon after my arrival in Lombok that if I went out after sunset (magrib) I should always be careful, especially if I was to wear a perfumed or sweet smelling deodorant. Sunset is the time when jinns come to life (awaken) and they are ravenous. Sweet smells are believed to cause jinns to salivate and they are particularly attracted to the sweet smell of rampe (water in which fresh flowers have been steeped) or sandalwood incense. If you want to keep jinns away from you, you must always bath in salt water and eat lots of strong smelling food, especially food containing onion and garlic because jinns hate salt and strong or sour-smelling vegetables, such as garlic, turmeric and lime leaves.

When I asked Bado what the jinns ate apart from sweet smells, he looked at me deep in thought and replied casually ‘baras kuning’ (yellow rice).

‘We often give them offerings of yellow rice to show that we are their friends.’

If they have no mouths, I enquired, how do they eat?

‘They have mouths but no lips.’

At this point Bado drew a sketch to show me what a jinn’s face looked like.

The fear of jinns prevents young people from congregating around the village after dark.

Jinns play an important role within the Sasak village structure. Not only do they make the villagers aware of where they are walking, they also play an important role in social control. They prevent villagers from going out after sunset (thus preventing illicit sexual liaisons after dark). It was because of jinns that everyone was safely at home after sunset.

By now, everywhere I went, people spoke of jinns as if they were their next-door neighbours – which indeed they were (and in many places still are). To the Sasak villagers, jinns inhabit an invisible parallel universe to their own, that awakens at sunset and retires to sleep at dawn. Every villager I spoke to agreed that jinns may live close to you but you must never take them for granted. They are unpredictable non-human beings and, if you get too close to them, they may physically attach themselves to you or a member of your family with sometimes dire consequences. When a jinn attaches to a victim, it becomes like a second shadow, burdening its host until it finally kills him (or her) – unless you visit a “Belian Jinn” a traditional healer who specialises in removing these invisible beings from the human body. Jinns, according to Bado, may act like humans, have the same religion, the same name and even the same morality and culture but don’t be deceived, he said, ‘they are very “bebahaye” (dangerous).’

Unseen by the human eye they may be disturbed (accidentally) or even hurt and when this happens they become revengeful, causing illness and sometimes even death to their unsuspecting victim. It is for this reason that villagers are consciously aware of every step they take while crossing the domain of the jinns within their village boundaries. As Bado pointed out:

‘When I was a child, I remember my mother constantly telling me not to go to the gardens by the river. This place, my mother told me, was a large jinn village and marketplace — it was a dangerous place that children were bebalaq (forbidden) to enter as they may unwittingly hurt a jinn or even destroy their house or garden. Jinn anger directed at a child can cause illness and death – many children in my village have died from being ketemuk “touched” by jinns.’

Bado spoke in a solemn tone about the constant dangers of jinns in the everyday life of his village. There were no doubts in his mind that there was an ever-present threat from potentially harmful jinns that lived within an invisible parallel world within his village. To be aware and vigilant was his only means of protection both for himself and his family.

Stories about jinns

The Truck Driver

Sasak villages have many densely vegetated places where jinns even to this day are said to inhabit. When Bado started to answer my questions about jinns it was hard to contain his anxious discourse on the subject. He went on to narrate story after story of dangerous encounters which he had heard about involving unseen beings in local and distant Sasak villages. One story that everyone related to with grim horror was the tale of a truck driver who was delivering goods to a remote village in Northern Lombok. After a long drive from Mataram the truck driver became very tired and decided to pull off the road and rest for a while. He found a clear shaded place and drove his truck into this space to get away from passing traffic. He soon fell asleep and never awoke to reach his destination. Two days later he was found dead in the cabin of his truck with the most horrific and tortured expression on his face. When they brought him back to his village the local belian jinn looked at the tortured facial expression on the dead man and knew at once that the truck driver had been killed by jinns. He announced to the villagers that he could read in the tortured man’s face that he had destroyed (unwittingly) the Datu jinn (head jinn of the village), his house and his two children. The Datu jinn’s brother was so enraged at the death of his older brother that he swore an oath on his family’s sacred kris (a large dagger with a wavy blade) to avenge his brother’s death. This he did. While the truck driver slept soundly in the truck cabin the brother entered a dream in the unconscious mind of the sleeping man and tortured him to death.

Throughout my travels in Western Lombok I have heard numerous versions of this moral tale. All emphasise that it was the truck driver’s own lack of attention that caused his agonising death at the hands of a revengeful jinn. The moral to this story is that villagers must at all times be aware and considerate of the presence of other human and non-human beings which inhabit their world.

The Fisherman’s Tale

P.J. a small thin man in his early 60s scowled at Bado when he asked him to tell the story of his son who mysteriously disappeared while fishing down by the river two years earlier. The elderly man proceeded to tell the tale of a young fisherman who he believed was enchanted by a beautiful jinn woman. His son would meet the jinn woman and her chaperone at the same place every day while fishing. He fell madly in love with the beautiful jinn woman and asked her father if he could marry her. To his surprise the father agreed, with one condition – that he was to leave the world of humans and enter the world of jinns and stay forever. P.J.’s son did not mention his proposed marriage to anyone as he was sworn to secrecy by the magical powers of the ijnn woman’s father.

No one has seen the young fisherman for two years and all believe that he has left this world and gone to another. According to P.J. his son has become very wealthy and is now the father of two jinn children. As P. J. related the story he did not find his son’s disappearance a particularly strange or unusual happening. He felt secure in the idea that his son had a family and was safe and secure in a co-existing parallel world. Stories like this help to rationalise a situation where there is otherwise no plausible explanation and they give solace to parents whose children have mysteriously disappeared. The whole village believed this story. (Field notes Ken Macintyre 1996)

The mysterious disappearance of individuals from Sasak villages was believed to be unquestionably the work of jinns.

Throughout my stay in Western Lombok I heard many stories of men (surprisingly none of women) who had mysteriously gone missing for up to ten years or more. In some cases they reappeared, as if out of nowhere, looking clean and affluent. However, within a matter of weeks of their return, they were prone to becoming depressed and impoverished. This was a common theme throughout village narratives of young men who had disappeared and years later reappeared from the ‘other world,’ reinforcing the idea that a relationship with a supernatural being usually ends in misfortune.

Mulut and her Jinn Advisors

Jinns even to this day may explain misfortune and sickness. The scale of jinn-induced ailments may range from simple headaches to acute disorders of body and mind, sometimes resulting in death.

Mulut was an illiterate Sasak woman in her late thirties, the wife of a poor tenant farmer with five young children. Her husband, like many other tenant farmers, was caught up in a cycle of chronic debt involving unscrupulous landlords and moneylenders. The family had been living in dire poverty for a number of years and Mulut’s only means of survival was collecting the sparse left-over grains of rice from the sawa (rice fields) that had fallen during harvest.

According to Mulut, the jinn came to her at 2am one morning when she was breast-feeding her youngest child. A fashionably dressed jinn appeared out of nowhere and introduced herself as Patimah Sakti. She then lit an American cigarette and spoke gently to Mulut, telling her that she would have no more worries and was soon to become a wealthy woman. The jinn woman then vanished. Mulut thought she must have been dreaming or imagining it.

The next evening when Mulut was trying to scrape together a few grains of rice to cook for her family, she said she had a strange feeling before opening the rice pot. When she did open it, a miracle happened from God. The rice pot was filled with soft white rice. From that time onwards at every meal the rice pot was full and other foods such as fish, fruit and vegetables miraculously appeared in her kitchen.

About a week after her meeting with the jinn woman, Mulut was in her garden collecting some firewood when Patimah Sakti and her two sisters appeared before her. Patimah introduced her sisters as Putikah Sakti and Patiker Sakti and then told Mulut that she was to become a healer (dukun) under the supervision of all three jinn women. Mulut’s jinn advisors serve separate functions in her healing practice: Patimah Sakti is the guru teacher, Putikah Sakti removes the illness and Patiker Sakti makes the tumpu or medicine. Throughout the healing session Mulut smokes cigarettes and babbles in an unrecognisable language to her jinn mentors which she tells me is Bahasa jinn or “jinn language.”

Mulut has no fear in attempting all manner of traditional healing on every part of the human body. She employs every technique imaginable from pressure point massage therapy to detecting minute supernatural beings using a surgical syringe to extract offending particles and curing chronic eye conditions using Chinese-derived medicines containing the regurgitated inner lining of the nest of the Asian swift known as sarang borong. I was told that there is no malady that the cigarette smoking dukun and her three jinn consultants could not remedy. She has clients arriving from all over Indonesia seeking her help and she is now a wealthy woman. (Mulut would not allow us to photograph her image as she thought that the camera might diminish her powers and expose her jinn mentors).

Mulut’s jinn gurus are from a privileged aristocratic family that resides in a fashionable jinn suburb at the foot of Mt Rinjani known as Rangkung. Mulut spoke of her jinn mentors as if they were real people with individual personalities. She describes Patimah Sakti as deep and meditative and in tune with the spirit world; Putikah Sakti as soft and silent and Patiker Sakti as a headstrong woman who will argue and fight to defend her own opinion.

These spiritual mentors, according to Mulut, are with her at all times during her consultations with clients throughout which process she is constantly talking to them in jinn language. Throughout my interview with Mulut I kept thinking to myself ‘this is incredulous’ – was Mulut merely putting on an act to impress her clients or was she in some mysterious altered state of consciousness? I never did find out. The story of Mulut is an incredible one. Whether her personalised jinns are a product of her imagination or something else belongs to the anthropology of the beyond. One thing for certain is that the prophecy of the jinn had come to fruition and Mulut was now a wealthy woman.

‘Jinn society was more than an omnipresent parallel universe, it was a social control mechanism and an invisible explanation of the impossible.’ (Macintyre and Dobson 1996 unpublished field notes).

The belian of the sacred “jinn wood”

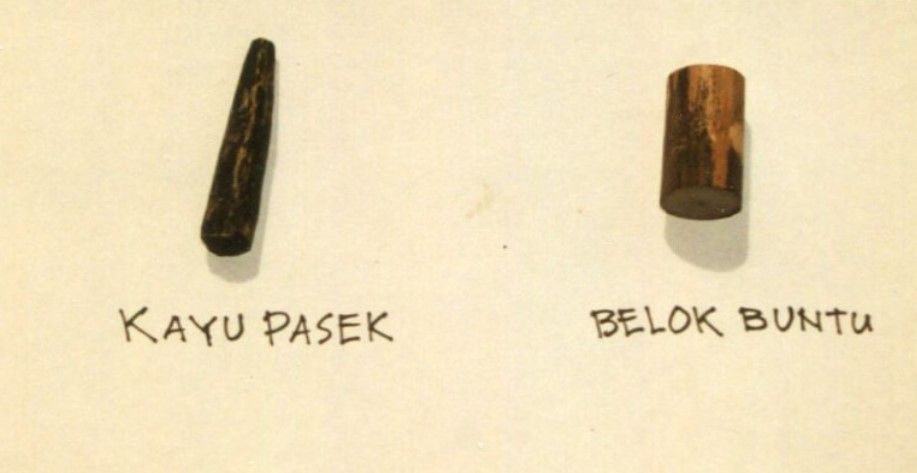

Pokop told me that he was in his mid-sixties but he looked well over seventy-five years of age when I met him in a Sasak village south of Ampernan. He claimed to be a belian jinn with special ilmu (knowledge) for defusing a type of black magic known as sokeq.

‘I was not always a Belian’ Pokop revealed to me. ‘It was not something that I inherited; it was assigned to me in mid life. I was once a hard working rice farmer.’ He began telling me his story which goes as follows. One day he and his labourer were digging a well when they came across an old blackened tree stump. They worked on the stump for many hours but only managed to remove a very small piece of the wood. The stump was indestructible. The following day they tried to cut the roots with an axe but this only blunted the blade.

I left my labourer at the worksite while I attended some important business in Ampernan late morning. Later in the day I received an urgent message that my assistant had been killed in a mysterious accident at the site and his nephew who had been helping him was seriously ill.

Pokop could see no reason as to why this should have happened. It was only an old tree stump and he had removed many similarly obstructive tree roots in the past. He had an ominous feeling about the accident and consulted his local belian who was a specialist in jinn behaviour. The belian visited the place where the accident had happened to assess the cause of the accident. He immediately recognised this as a sacred place where jinns had performed rituals involving this ancient tree. Pokop decided not to continue trying to remove the old stump as he feared for his own life. He knew better than to disturb or anger the jinns as they could be vengeful. That night he had little sleep but at around two in the morning as he drifted off to sleep an irate jinn elder visited him in his dream. The jinn told him that his labourer had been killed because he had tried to desecrate, albeit unknowingly, a sacred jinn shrine by attempting to remove the remains of the sacred tree. The jinn revealed to Pokop in his dream the ilmu or knowledge of this sacred wood and its restorative healing powers.

Kayuk (wood) from mystical or dangerous places such as this one was often used in black magical potions.

Several days after the incident Pokop visited his brother in a neighbouring village. The brother was depressed and had no desire for his young wife. As the brothers drank tea, Pokop put a scraping of the sacred wood into his brother’s cup without him noticing. That night his brother had an erotic dream about horses mating and once again was filled with desire for his young wife. From that time on the splinter of sacred wood transformed the direction of Prokop’s life from that of a farmer to a healer (belian). He never returned to the place of the sacred jinn shrine heeding their warning that harm might come his way and even death, if he were to return. Today Pokop is a successful belian who specialises in treating male impotency. He proudly told me:

The conditions I cure are all related to desire and sexuality. This malady affects all men. The medicine of the jinn root gives back power and vitality. The minutest quantity of the root puts power in the penis of my clients.

Pokop’s clientele is exclusively male. Most of the men he treats have more than one wife (as accepted in their culture) or are involved in extra-marital relationships. He said that when a man has more than two wives or lovers, these women usually compete for the husband’s attention. If they don’t get sufficient attention, they often become resentful or jealous of the other wives and in such cases they may visit a dukun pelet or dukun seher (shaman specialising in black magic) or dukun santet (sorcerer, sex magic) who will prepare a black magical potion to diminish the husband’s sexual drive.

Pokop told me that he had cured more than 200 patients in his time and all of them involved black magic. He revealed to me that he never tells his patients that it is their multiple wives that are their problem for he feels that this would humiliate them. He tells them that their condition comes from God or Allah. He said:

‘I understand if a patient comes to me at least three times, his condition is normally related to black magic. If the patient’s condition is difficult to diagnose, I dream about it and in my dream it is revealed to me that the person’s condition is caused by a type of black magic. Sometimes I feel that there is a reason why the black magic was put on that person and I agree with the reason but I still have to treat them and remove the magic. Impotence caused by black magic is simple to cure for most black magic comes from sokeq and sokeq comes from wood (kayuk). This is easy to counteract using the power of my jinn wood which is the most potent of all wood. It is not the wood that I worry about but the jampi or spell for that may involve a supernatural agent (such as Satan or jinn). These jampi can be difficult but they are the creation of men (dukun) and if men created them, more powerful men can defuse them, especially with the help of God who will make the final decision.’

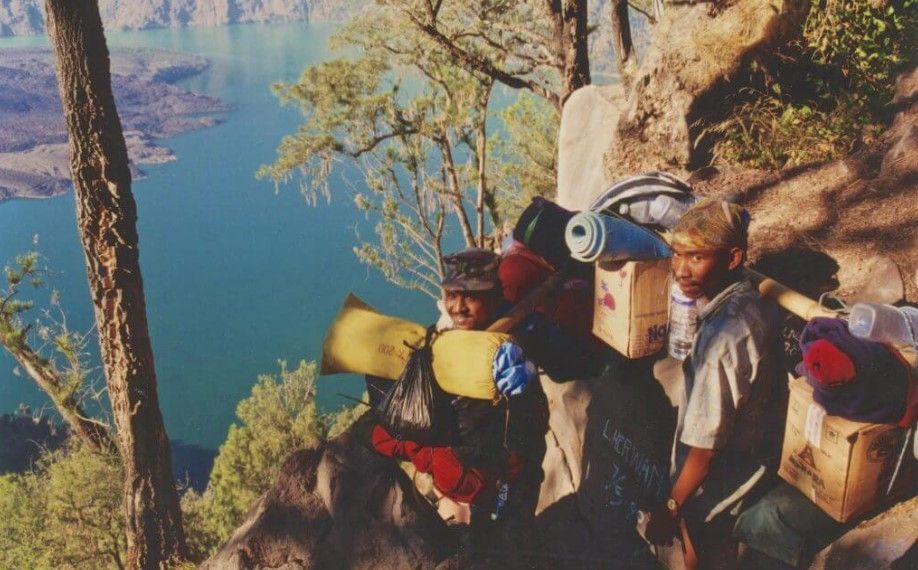

Climbing Mt Rinjani

During our spiritual pilgrimage to the heartland of the jinn kingdom high on Mt Rinjani, in Northern Lombok, an incident involving a human-jinn interaction occurred. It happened while Bado and I were negotiating a narrow pathway above a steep ravine. Bado was walking in front of me carrying my camera bag over his right shoulder. Everything seemed perfectly normal when all of a sudden Bado started to lose his balance and fall off the path towards the ravine. Some unconscious reflex action made me grab at the camera bag strap over Bado’s shoulder as he fell. The next thing I remember is hauling Bado’s struggling body back onto the narrow pathway. His face was ashen white. He looked terrified and began to shiver as if in shock. He looked at me and said ‘They pushed me off the path, Mr Ken.’ ‘Who did?’ I asked incredulously, thinking to myself that the shock of him almost falling to his death must be causing him to rave. ‘I felt them push me’ he said. ‘Who pushed you?’ I asked. He did not answer. I said ‘it’s okay you slipped off the pathway, no one pushed you. You’ll be okay.’ However, my reassuring words did not alleviate his anxiety. After a short rest we continued on our way before the onset of darkness.

As soon as we caught up with the other guides and porters, all activity came to a halt and a deep discussion ensued between them. It was intense and I think somewhat analytical, taking apart the incident bit by bit, place, time of day and what Bado was thinking when he was “pushed” off the pathway. To me it had been a simple case of Bado losing his footing on a precarious pathway. This was not the case according to our expert guide and spiritual ranger Dana who believed that what Bado had experienced was a common occurrence in the kingdom of the jinns on Gunung Api (mountain of fire, volcano). Dana explained that Bado had encountered a noble jinn landowner and his two sons using the same pathway, walking in the opposite direction. Bado, not fully understanding the code of etiquette required of these aristocratic jinns, had omitted to ask permission from the local jinn landowner and to announce that he was about to travel the pathway with a foreigner. He had (albeit unintentionally) offended the noble jinn and his two sons were angered by Bado’s lack of courtesy and disrespect to their father, so they pushed him off the path towards the precipice.

Bado sat despondently listening to Dana’s explanation of jinn society on the sacred mountain. According to Dana, jinn society was ancient and they still practised Perwangsa (noble or aristocratic caste system) whereby powerful jinn families still controlled large tracts of land and jealously guarded their territory from outsiders. Bado was one of the lucky ones. ‘Many Sasaks have been killed by jinns in this place,’ said Dana. Bada never mentioned this incident again throughout the remainder of our trek but I could see from his demeanour that he was profoundly shaken by the event.

Mark meets a jinn couple while trekking on Mt Rinjani – 1997

Mark sat bent over a large tree stump with his head resting in his hands. ‘Hey what’s the matter I asked…are you hurt’? He looked up at me, his face pale and streaked with tears. ‘No, I don’t think so.’ He said despondently ‘I grazed my arm when I slipped down this embankment.’ He held out his right arm for me to see a deep graze near his elbow. There was very little blood or dirt on the wound, in fact it looked as if it had already been cleaned ready for dressing. ‘That looks fine to me’ I said ‘No pain’? ‘No,’ he replied. I asked him if he had cleaned the wound? ‘No,’ he answered hesitantly. ‘It was a little old woman who washed my arm and put some medicine on it.’ ‘What little old woman’ I inquired? ‘They left as soon as you arrived,’ said Mark. Things were starting to verge on the incredulous, so I abruptly asked ‘What are you talking about’?

‘There were two of them, a little old woman and her husband. He was very old with long white hair and was wearing a sarong and waistcoat—and she was very kind. The old man was standing where I fell. He helped me up and sat me on the tree stump. He told me not to worry, everything was going to be okay. The old lady washed my arm with water and a white cloth that she kept in a large shoulder bag. Then she rubbed some medicine on the graze—it didn’t hurt at all.

He lifted his arm and pointed to where the medicine had been applied.’They were both very kind and told me they would stay with me until you arrived.‘ ‘How did they know I was coming, did they speak English?’ ‘I don’t know’ Mark replied. ‘But I understood what they were talking about.’ He must be in shock I thought to myself. Or was I in shock? Everything to Mark seemed perfectly normal. I could not restrain myself from asking him in what direction they went when I arrived. ‘They just vanished’ he said ‘they told me they were going.’

Mark was only ten years old and I began to wonder whether his current enthusiasm for Harry Potter novels had coloured his imagination?

When I related this story to our Sasak guides who were close by when the incident happened, none of them was surprised. It was as if this was a common occurrence on Mt Rinjani —- the mountain being the ancestral home of the jinns.

There is a belief among local Sasak people that people (including tourists) who climb Mt Rinjani without a “spiritual ranger” or without taking into account and properly respecting the spiritual significance of the place to its jinn inhabitants, risk their life or a serious accident. Climbers must be constantly aware that this is the realm of the jinns and must be respected. Deaths and accidents on Mt Rinjani are mostly attributed to the person’s naivety with regards to the required protocols when entering the traditional territory of the jinns.

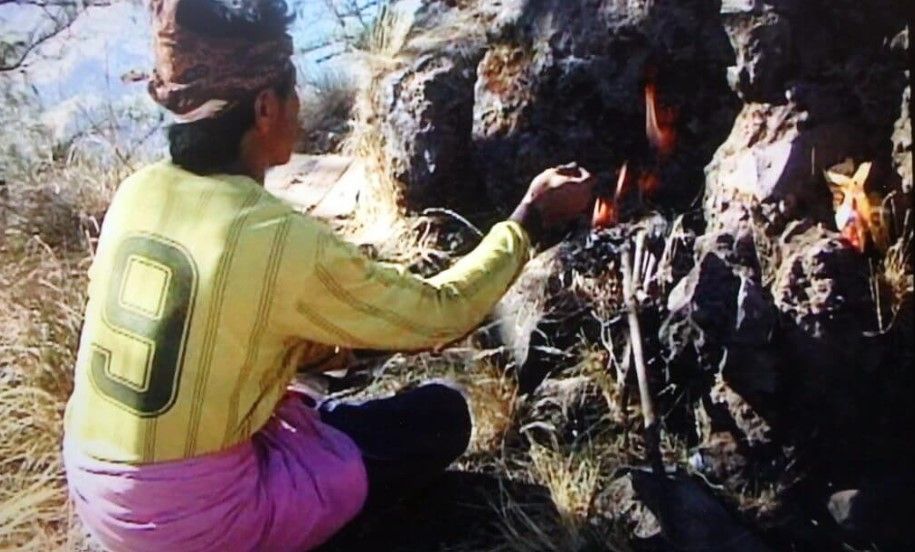

It was for this reason that our pilgrimage with our Sasak guides and assistants involved a “spiritual ranger” who performed the rituals necessary to enter the gateways to the different administrative districts of the jinn kingdom on Mt Rinjani. It is our belief as anthropologists that when we enter the spiritual domain of other cultures that we try to respect their beliefs and traditions and travel with them.