Beyond 2000 – Future Directions in Marine Education

Ken Macintyre April 2000

Overview

Paper presented at the Annual Marine Education Society of Australasia (MESA) Conference at Notre Dame University, Fremantle, Western Australia

This paper focuses on the process of generating community awareness of the conservation value of our coastal and marine environment at Cottesloe, and how the community develops a sense of custodianship over its marine resources and protects its valued resources through education and ‘soft’ policing’.

Generating Community Awareness of the Conservation Value of the Cottesloe Reef System: An Anthropological Perspective

How It All Began

How did it all begin? It began with 4 concerned snorkellers who had noticed a number of changes on the Cottesloe reefs such as reef degradation and a decline of large reef fish populations, especially predators. The dwindling numbers of large reef fish were seen to be the result of the long term effects of spearfishing. In addition to this, there was concern about the excessive growth of Cladophora, a filamentatious green algae, which was starting to smother the reefs and seagrasses. Long green ribbons of Cladophora were particularly noticeable at Cottesloe in February and March 1999, and this is highlighted in the film produced by Rowley Goonan at that time.

Meeting the Stakeholders

In consultation with Dennis Beros from the Australian Marine Conservation Society (ACMC) it was decided that we should hold a focus workshop to inform key stakeholders (government and non-government organisations) of the Cottesloe Marine Protection Group’s proposal to seek some form of Marine Protective status for the Cottesloe reefs and waters. The meeting held on Sunday 14th February 1999 was facilitated by Dennis Beros. The results of the meeting were that there is a bigger picture out there of pollution, development and increasing population pressures on our beaches and marine environment, and ‘yes’ the community should be encouraged to take the initiative to protect assets such as beaches and reefs. These popular notions of ‘community stewardship’, ‘community control’, ‘community ownership’ and ‘sense of place’ were all embraced with great enthusiasm. Alas, at this time, we did not realise that these were ‘buzz’ words used by government departments stripped of resources and enforcement officers who could find no means of controlling their given domains.

The idea of ‘giving it back to the community to control’ gives one a nice warm feeling but behind it all is the emptiness of political rhetoric. It was like all these government departments had a brainstorm one day and came up with the idea that the most efficient way of minimising the extra costs associated with conservation trends of the new millennium was to pass the responsibility on to the community. This is happening increasingly in other spheres as well, such as employment and crime control.

It is really unclear what the term ‘community’ here means. Does it mean a community of interest groups who share a common interest in the Cottesloe coastal waters, or a community of local residents, or the wider community of Cottesloe beach and reef users or the Western Australian community in general? We have found that when the term ‘community’ is used in relation to our Cottesloe reef conservation project most people think of it as a localised group consisting of Cottesloe residents who live in proximity to, and have an affinity with, the coastal waters. Indeed ‘community’ must have a different definition in the bureaucratic sense because when a ‘community group’ wishes to apply for ‘Coast and Clean Seas’ funding under the Federal Government Natural Heritage Trust it must apply as a ‘consortium’ which includes local government, government and non-government corporate bodies. Whatever definition we use, ‘community’ is certainly a ‘feel good’ concept that is often touted to attract government funding and it is a convenient way out when government resources run dry. For the purpose of this paper the term ‘community’ applies to the local community of Cottesloe and the wider community of Cottesloe beach and reef-users.

At the workshop, a rather daunting picture was painted, especially for a small community group of volunteers who were trying to conserve an inshore reef system at Cottesloe. What seemed to complicate things was the overlapping jurisdictions of the different government organisations such as Fisheries WA, the Department of Conservation and Land Management, Department of Transport and the Fremantle Port Authority over the coastal waters yet none have afforded any formal legislative protection over the Cottesloe reefs and waters to protect them from either pollution or human predation.

By this time we knew that CALM would not consider another Marine Reserve in the Perth Metropolitan Area owing to the establishment of Marmion Marine Park in the 1980’s and besides Cottesloe was not on the Wilson list of potential marine reserves. Colin Chalmers from Fisheries WA pointed out that a model known as the Fish Habitat Protection Area (FHPA) was available within the Fish Resources Management Act that could be used and promoted by communities to protect marine resources.

Where Do We Go From Here?

‘At the end of the day’, as we walked out of the workshop with ‘the big picture’ looming before us, and the popular yet undefined notion of ‘community stewardship’, and confusion as to which direction to take, we asked ourselves, ‘where do we go from here?’ It was at this time that our group started to develop conflict in which approach we should take. Should we go public and let the community know about our proposal for a Marine Protected Area (MPA) at Cottesloe and enlist community support, or should we remain a small lobby group politicking and lobbying the larger organisations for their support.

Beach Interviews and Community Perceptions

‘It’s still the same as it has always been’

‘We have the cleanest waters in the world and that there is no pollution at Cottesloe’.

‘There used to be a lot of shells on the beach and the rock pools always had small fish in them’

‘They used to catch big fish on the reef – there were blue grouper, jewfish and some big sharks would come in.’

‘There were always lots of periwinkles and small mussels on the rocks – they’re not there any more.’

In order to determine which direction the group should take, we decided to test community reaction to the idea of a Marine Protected Area at Cottesloe and to gauge the extent of local knowledge of the Cottesloe reefs. This was achieved through informal interviews with beach and reef-users at Cottesloe in February and March 1999. What was apparent from these interviews was a general lack of local community knowledge about the biodiversity and conservation value of the Cottesloe reefs. Of course there were some underwater enthusiasts who were familiar with the reefs and had noticed changes in the area such as a decline in resident reef fish populations and the growth of Cladophora over the summer months but they thought this was perhaps a natural phenomena.

Many of the people interviewed were under the impression that the Cottesloe reefs and waters were already protected by government regulations and it came as a shock to them to realise that the only protection to the area was a Town of Cottesloe prohibition on the use of spearguns and gidgees, and Fisheries WA regulations which managed abalone and crayfishing through a license system.

The survey also revealed that some beach users were unaware of the existence of reefs at Cottesloe. This is probably explained by the fact that in the past most of the focus at Cottesloe was north of the main groyne and the majority of people who visit Cottesloe Beach only see what’s above water. They don’t know what lies below.

Overall, the interview survey results showed a diverse range of community views and beliefs including:

- a lack of awareness of the existence of any reefs at Cottesloe

- nothing has changed, it looks the same as it has always been

- fish and fish habitat at Cottesloe were an unlimited resource which could sustain human impacts such as pollution, spearing and collecting, no need to act

- the sea will look after itself

- fewer large reef fish around

- a decline in shell, crab and perriwinkle populations

- the Cottesloe reefs and waters are already protected by government regulations

Many people were surprised and even shocked to hear that spearfishing still occurs at Cottesloe. They said that they had always been under the impression that spearfishing was prohibited at Cottesloe under government regulations.

What was very clear from the interviews was a lack of public awareness of the connection between land and sea. Few people were aware, or had ever thought about, factors which may impact on the inshore reefs at Cottesloe, such as chemical fertiliser usage on their lawns and gardens, stormwater drains, underground water, sewerage outflows, Swan River outfall and algae growths on the reefs and seagrasses. Few people were aware of the fact that there are fourteen stormwater drains along the Cottesloe foreshore which discharge directly into the sea.

It started to dawn on us that we had a huge task ahead of us of generating public awareness of the conservation values of the CRS. Without community awareness, support and involvement, we knew it would be pointless pursuing a Marine Protected Area at Cottesloe. However, not only did we have to prove to the general community that the Cottesloe reefs, sea grasses and marine life were worth protecting and preserving for present and future generations but we had to prove to a government department – and key stakeholder groups – such as Recfishwest, the Recreational Fishing Advisory Council, the Western Australian Fishing Industry Council and others – that the Cottesloe reefs are worth protecting and preserving.

As one local resident stated: ‘Why don’t you bring the Minister down here and show him the reefs, then he can see for himself how beautiful the place is and worthy of protection’. We thought: ‘If only it were that simple.’

Tell Me, Is This A Marine Park?

Soon after the workshop Dr Barb Dobson and myself conducted an informal survey in the Marmion Marine Park between Triggs and Burns Beach to ascertain whether members of the community and visitors to the area understood that these coastal waters were protected under the CALM Act. Interestingly, the results of our survey revealed that most people interviewed, especially those using the Beaumaris and Burns Beach areas (to the north of Marmion), were not aware that Marmion Marine Park extended beyond Marmion. When asked ‘Tell me, is this a Marine Park?’, the common response was: ‘I’m not sure.’ Furthermore, when we asked them if we could use spearguns in the area, most said they thought it was okay as they had seen the occasional spearfishermen there. When we interviewed some of the residents at Burns Beach, they expressed their frustration at the time taken by Department of Fisheries and CALM officers in responding to their calls. They said that in some instances when people were observed illegally spearfishing or crayfishing, the officers took 3-5 hours to arrive, by which time the offenders had disappeared, and the community had no power to enforce these government regulations.

Our analysis of the survey results suggests that Marmion Marine Park was imposed from above onto a largely uninformed local community which had not been prepared for, far less aware of, the extent, boundaries and protective prohibitions which applied to the Marine Park. A number of people interviewed thought that Marmion Marine Park applied only to the Marmion coastline. There did not seem to be any identification or sense of community ownership between the beach- users interviewed and the Marine Park itself. It did not belong to them but rather was administered by a government agency. Furthermore, they were not only uncertain of the boundaries of the Marine Park but they seemed to have little idea of the extent of the biodiversity within the Marine Park.

I am not saying that there was no community consultation prior to the establishment of the Marine Park. Indeed there was. According to the Proceedings of the Seminar held at the Marmion Angling and Aquatic Club on 12th June 1985 there were representatives from at least 40 different interest groups, organisations, government departments, universities and political parties involved in discussions relating to the proposed M10 Marine Park. However, my questions are:

- Where were Mr and Mrs Public who use the beach every day?’

- Were they involved with other community users in the decision-making processes relating to Marmion Marine Park?

- Were they involved in any long-term community education programme about the reefs?

- What was the level of public awareness of the conservation and natural heritage value of the Marmion reefs?

It is all very well for a government department to advertise Public Meetings or to invite public submissions on Draft Management Plans but before there is any involvement by the public in this process, there must be an informed public.

How can one expect the wider community of users to be involved in the care and protection of the Marine Park if they have little or no awareness of its marine biodiversity and conservation value?

The Need for Community Custodianship

It was after this brief field experience in the northern reaches of the Marmion Marine Park that our group decided that Cottesloe was not going to be a ‘paper park’ and that our focus would be to generate community awareness of the biodiversity value and vulnerability of the Cottesloe reefs and coastal waters, and most importantly to engender a sense of ‘community custodianship’. The term ‘custodian’ is used here in the same sense as in Aboriginal culture. A ‘custodian’ is a person who cares for and protects an area of great sensitivity, such as a sacred site, food source or valued habitat. A ‘custodian’ is not an ‘owner’ but rather a site ‘protector’ or ‘carer’ who lives locally and is responsible for the ritual maintenance and protection of a specific site or area. Most importantly, the custodian is responsible to a wider group of people who also have strong connections to the area, even though they live at a distance from the site. In order to achieve ‘community custodianship’, our group had no choice but to go public about its FHPA conservation aims.

Going Public

Our group decided to go public and to enlist community support through a series of public meetings and regular media coverage. The rationale behind this was that it was pointless to work within the community unless the community embraced the conservation principles of the group, and most importantly, we believe that it is only if the public is informed about the habitats and creatures that live in the Cottesloe Reef environment and understand how their actions may threaten this marine life, that the community will adopt attitudes and behaviours that are consistent with the aims of marine conservation.

We held our first public meeting at the Lesser Town Hall, Cottesloe Civic Centre on 10th March 1999. The purpose of this meeting was to gauge public reaction to our Marine Protected Area (MPA) proposal and to determine the level of community awareness of, and interest in, the natural heritage and conservation value of the CRS. In order to advertise the meeting, flyers were designed and a number of questions were posed to attract community attention such as:

- ‘Do we know what is going on in the coastal waters around Cottesloe?’

- ‘Do we understand how the biodiversity of marine life at Cottesloe is being depleted by spearfishing and the collecting of marine creatures?’

- ‘Do we understand how small a quantity of nutrients (from stormwater run-off, fertilizers etc) can dramatically change the marine environment from one of a healthy reef system to one polluted by the excessive build-up of algae.’

These questions were designed to elicit an interest in the Cottesloe marine environment.

The weedy seadragon was adopted as the Cottesloe Marine Protection Group’s official emblem as Cottesloe was a recognised hotspot for this fascinating creature and our group believed that its presence suggested a healthy reef and seagrass system. We also thought that the seadragon would appeal to the general public and become an icon for the Cottesloe waters.

At the public meeting expert speakers gave talks on the biology and conservation value of the Cottesloe Reef System (CRS). Rowley Goonan’s documentary video of the Cottesloe Reefs called ‘Between the Groynes’ was shown and experts and members of the public were asked to comment and ask questions about the biology and condition of the Cottesloe reefs. For many of the people who attended this meeting it was their first time to view what was under the sea at Cottesloe.

It was at this time that there was a very bad bloom of Cladophora at South Cottesloe and many viewers were shocked by the long green ribbons of filamentatious green algae that was attaching itself to the reef and sea grasses. Some people were made aware for the first time that along the Cottesloe shoreline there were fourteen storm water outlets which discharge directly into the Cottesloe waters.

A Fisheries WA representative outlined different models of protective legislation which could be used to protect the coastline. The Fish Habitat Protection Area model was voted unanimously as being the most appropriate form of legislation for protecting the Cottesloe reefs and waters. A steering committee was established which included representatives from Fisheries WA and specialists in the fields of environmental science, marine biology, marine ecology, coastal geology, anthropology and community relations.

At the conclusion of the meeting all people agreed that the wider community of beach users and reef users should be made aware of the vulnerability of the Cottesloe coastal waters to pollution and human predation, and they urged that some form of management and legislative protection be achieved as soon as possible.

It was emphasized that protective legislation alone will not protect the reefs as the resources needed to officially police the area would put a strain on the already limited Fisheries WA staff resources. Community awareness and involvement through education and ‘soft policing’ by community members in cooperation with the Town of Cottesloe rangers were seen as critical to the success of any protective legislation.

Increasing Community Awareness and Involvement

Our informal beach interviews and public meeting established that there was generally speaking a low level of awareness and knowledge within the beach-user community of the conservation value of the CRS. The problem which our group now faced was which methods should be used to inform the community about the rich biodiversity and natural heritage value of the CRS to enable the community to view this as an asset worth protecting for present and future generations. A variety of means were used for this purpose:

- media publicity – ABC television and radio, Channel 9 ‘Just Add Water’, 6NR, RTR FM, 100 FM, Marine and Coastal Community Network’s email system and ‘Sandgroper’ and ‘Waves’ publications, Fisheries WA publications including Western Fisheries magazine, AMCS Newsletters, Julie Bishop Newsletters, Colin Barnett Newsletters, The West Australian, Sunday Times, Post newspaper, Local News, Perth Weekly, the Chronicle Community Newspapers, Town of Peppermint Grove/ Cottesloe and Mosman Park Library displays, Scotch College newsletters & power point presentations, S.Hildas newsletters, andTown of Cottesloe ‘Civic Centre News’.

- documentary film presentations,

- broad-based community consultations and on-going beach interviews,

- school visits and school projects on Cottesloe marine conservation issues such as reef preservation, beach litter surveys and stormwater problems,

- public meetings (10th March, 30th June and 7th December 1999)

- public workshops (14th February and 13th September 1999)

- Reefwise Newsletter

- Seadragon Festival

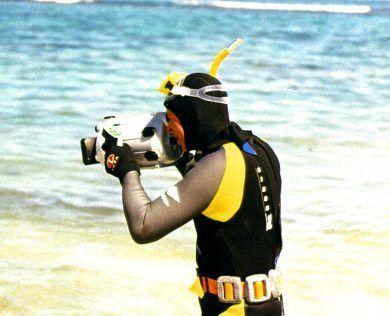

The Community Takes a Dive

By far the most powerful tool in raising community awareness of the conservation value of the CRS has been underwater videography. Over the past 14 months Rowley Goonan’s three documentary films which highlight the diversity of marine life on the Cottesloe reefs have been shown in schools, public meetings, workshops, government departments, festivals, displays and conferences. These films have been instrumental in raising public awareness, as evidenced by the following verbatim comments:

‘I was very impressed. I had absolutely no idea as to the extent of the marine life which existed at such a short distance from the main Cottesloe beach.’ [Town of Cottesloe Mayor]

‘I never realized that we had this on our doorstep.’

‘These are the sort of things you go to the Great Barrier Reef to see.’

‘I’ve lived here all my life and the water never seems to change – I couldn’t believe the film when I saw it.’

‘We had better do something about it pretty soon or we’ll lose it’.

‘I’ve just spent two weeks diving in Thailand and we never saw anything quite like this.’

Throughout the process of generating community awareness, educating and informing the public of the biology, habitat, diversity and dangers to the reef system have been our primary focus. By giving the community an understanding and knowledge of what is living in the coastal waters off Cottesloe is to empower them to protect and care for this wonderful marine environment. It is imperative that the community adopts a protective approach to help restore and rehabilitate the reef fish populations. This can only be done by providing the community with accurate information, assisted by marine biologists, about the biodiversity and habitat on the Cottesloe reefs.

Other activities to raise community awareness, support and involvement included visits by CMPG to schools and kindergartens where films were shown and presentations were given. As a result of these visits schoolchildren and their parents became involved in related projects such as beach litter analysis, stormwater impacts, Cottesloe reef awareness surveys and marine conservation projects. These children disseminated information about the CMPG’s projects and activities to parents, grandparents and friends. Over the past 15 months the schools have greatly assisted in raising public awareness of the conservation value of the Cottesloe reefs.

Scotch College Junior School is a founding member of the CMPG and has been affiliated with CMPG since March 1999. The students have been involved in numerous activities including:

- the design and production of CMPG’s inaugural REEFWISE newsletter

- an original soundtrack composition to accompany spectacular segments of Rowley Goonan’s documentary of the Cottesloe reefs

- a Cottesloe beach litter survey and analysis

- the preparation of colourful artwork and music for the inaugural Seadragon Festival

- the preparation of a power point presentation for presentation to other schools

- boys in Years 6 and 7 became confident ‘ambassadors’ of the CMPG and contributed greatly in disseminating accurate information about the biodiversity and heritage values of the CRS.

A number of schools are now involved in CMPG activities in particular assisting with habitat mapping surveys and community awareness education. They also participate in the annual Seadragon Festivals to help promote awareness of the local marine environment through music and art themes.

Keeping In The Media Focus

Constant media coverage is essential in developing community awareness. Our group has sought publicity through local newspapers, radio and television, and let me warn you ‘it is not easy getting free advertisements for environmental causes’. Newspapers are in the business of making money and unless your article or letter is newsworthy, you don’t stand a chance. The public forgets very quickly a one-off event, so the group must generate community interest on a regular basis. This is hard work. Don’t expect all of your efforts to be published because there are lots of other community groups out there all competing for publicity.

Environmental Festivals

Big events within the community, such as environmental festivals which focus on the marine and related environments, are a highly effective means of disseminating information and generating community awareness. They are also a way of capturing media attention. At Cottesloe the Seadragon Festival held on 31st October 1999, which was coordinated by the CMPG in cooperation with the Town of Cottesloe,was one such event which successfully highlighted the beauty, biodiversity and vulnerability of the Cottesloe marine environment. pproximately 8-10,000 people attended the event. It was so successful the CMPG was awarded by the Town of Cottesloe the ‘Best Community Event of the Year’ at the Australia Day Awards Presentation Ceremony and it has now become an annual event.

Just remember that these festivals, if coordinated by the ‘new boy on the block’ are very hard work. You end up doing it all yourself and everybody waits to see if it is a success or not before they commit their support. Once its success is recognised and the Seadragon Festival becomes an annual event on the calendar, ‘the new boy on the block’ becomes only one of a number of community groups all wanting a slice of the action.

Cargo from Canberra

Public awareness, as we discovered, is not cheap. Soon after our group became established we were encouraged to apply for Federal funding under the ‘Coast and Clean Seas’ and Coastwest/ Coastcare Natural Heritage Trust programmes. The group becomes distracted with fantasies of obtaining large sums of money for research, monitoring, project officers, public awareness and so on. All our time was taken up by attending meetings on how to fill in grant application forms and listening to bureaucrats from Canberra talking about the allocation of millions of dollars for ‘worthy’ coastal and marine environmental projects. The term ‘worthy’ here encourages the group to spend hours conjuring up trojan horses that will attract the fancy of the Federal Minster.

The writing of grant applications is somewhat akin to the ritual formula of the cargo cultists of Melanesia. When the group performs the correct ritual, the cargo will come. If the application is unsuccessful, in most cases the explanation is that the form was not filled in correctly, or in terms of the cargo cult, it did not comply with the correct ritual formula or magical incantations. Like the cargo cult, when the grant is unsuccessful, the community group becomes angry, demoralised and resentful against others who may have been successful.

Whichever way you look at it, applying for grants and the long anticipatory wait for an outcome – and the uncertainty of it all – can be highly destructive and, like in the case of the cargo cults, can throw the group into a state of inertia. Everybody you talk to may say how admirable your cause is, but try getting them to help you and it’s another story. You are ‘the new boy on the block’ and you have to fight for everything that you get. Don’t expect any favours from the media, government bureaucracy or other related environment groups. You have to prove your credentials and be aware that the ‘new boy on the block’ is seen as a rival in terms of limited government grants. You are a threat.

Stakeholders

The task of proving to Cottesloe beach and reef-users that the reefs are worthy of protection and conservation is relatively easy because most people who use the area don’t want to lose it and they want to preserve it for future generations. However, the task of convincing stakeholders – such as the Recreational and Professional Fishing lobby groups – is another matter. They have vested interests in maintaining the status quo and do not wish to lose any access to coastal waters.

It seems that this stakeholder opposition is based on pinciples and the supposed rights of access for their members rather than the view that an area should be conserved and used in a non-extractive or non-consumptive way. When this matter was expressed to the local community at a public meeting the community could not understand why the rights of recreational fishermen should outweigh or be superior to the rights of community members who wanted to observe and conserve fish in their natural habitat at Cottesloe. In this paper I do not wish to debate the rights of ‘fishers’ as against conservationists. At Cottesloe we have tried to create a balance between these rights by seeking to prohibit boat fishing on the reefs at South Cottesloe but allowing recreational fishing to continue from the beaches and groynes. We believe that a balance can be achieved between fishers and conservationists.

Rather than letting stakeholder comments and criticisms destroy our group’s initiative, we decided to reframe the negatives and to reinforce the positive direction towards the conservation of the Cottesloe reefs by using local government beach by-laws and forming Volunteer Community Reefwatch (VCR) patrols to educate the public on the conservation and heritage value of the reefs. The installation of informative and colourful fish identification signage on the Cottesloe beachfront has greatly increased community awareness of the rich marine diversity of the CRS and the intentions of CMPG to establish a Fish Habitat Protection Area.

An indicator of the group’s feelings towards destructive practices on the reefs was demonstrated in February this year when newly installed signage at Cottesloe prohibiting spearfishing was defaced and destroyed by elements who disagreed with the signs. This caused community outrage and further reinforced surveillance of the beach by the local community and general public. Within three days new signs were erected by the Town of Cottesloe and people now talk with confidence about the area being protected by Council rangers and Voluntary Community Reefwatchers (VCR’s).

‘Us’ versus ‘Them’

One of the most common phenomena that community groups experience is that in order to survive the group must have a positive concept of itself in relation to all other forces that may threaten the group. In anthropological terms this is known as the ‘us’ vs. ‘them’ dichotomy. The ‘us’ being members of CMPG and ‘them’ being those groups that are perceived as being a threat to our group’s aims.

External threats may work in two ways. If the community group lacks the necessary skills, sophistication, expertise and resources to deal with external threats, the group may perceive it all as too hard and give up. This is a common response and is one of the main reasons why community groups often do not survive past the first twelve months. Group members become anxious, overwhelmed and leave the group, the rationale being that they were up against impossible barriers. In fact they are. The external threats invariably are larger interest groups that are well-entrenched, well-funded and politically motivated. This is commonly known as ‘the juggernaut effect’ where the community group is cruelly sacrificed to larger vested interest groups. On the other hand, the opposite may take place where the community group perceives the threat from outside as a challenge and uses this criticism as a catalyst to reinforce the group’s cohesiveness and solidarity.

The group may align with other like groups within the local community to fight the force. As the British social anthropologist Max Gluckman points out, beyond the family level ‘people seldom unite for anything, they unite against’ (Keesing 1981:285). Thus, in the face of opposition the community group, if it has the resources and determination, can use this external threat to its advantage by forming political alignments, increasing its membership and generating a sense of community pride and place in the area that it wishes to protect.

By now our group has become desensitised to hearing comments from stakeholders such as ‘Cottesloe’s marine life is not unique and that it is already represented in other areas such as Marmion Marine Park and Jurien Bay.’ One of our local residents aptly answered this by saying: ‘Why should we have to travel to Marmion or Jurien, when Cottesloe is at our doorstep?’ Similarly another resident commented: ‘Does this mean we have to destroy a marine habitat just because it is already represented at Jurien Bay? Where is the logic in all of this?’

When stakeholders question the ecological value of the Cottesloe reefs or state that ‘there is little evidence that the Cottesloe reefs have strong habitat value’ our response is that the CMPG has accumulated an extensive photographic and videographic database, which demonstrates without question the fish habitat and ecological value of the Cottesloe Reef System (CRS).

It shows that the Cottesloe Reef System:

- is a breeding ground for the weedy seadragon (Phycodurus eques).

- is a nursery area for Port Jackson sharks (Heterodontus portusjacksoni).

- is a squid breeding ground.

- contains 10 or more types of sea grasses and a wide variety of seaweeds

- contains a rich and complex biodiversity of marine life and habitat

- that shore reef systems (such as Cottesloe) accessible from the shore (with the exception of the tiny area in front of the Fisheries Waterman’s Laboratories) are not represented in marine reserves.

- is the only coastal reef system between Trigg and Rockingham.

- and the most remarkable feature of all is that the Cottesloe reefs are at the front door to our city.

Conclusion

As anthropologists it is easy to provide an “ideal” model for the establishment of a successful community action group. However, it is difficult to provide a formula for any specific group or project as sadly, in most cases “ideals” do not translate into reality. What I have tried to present in this paper are some of the difficulties which community groups face in their endeavour to protect an area of natural heritage significance to them. I have also provided a brief summary of strategies and actions which the CMPG has used successfully to generate public awareness. Our group has become pro-active in protecting the Cottesloe marine environment. By liaising with Fisheries WA and using the Town of Cottesloe beach by-laws, we have, in cooperation with Council rangers and our Voluntary Community Reefwatchers, dramatically reduced the incidence of spearfishing at Cottesloe.

Last but not least I cannot stress highly enough the importance of an informed public when it comes to implementing conservation management measures. Communities must be involved as custodians of their coastal domains. I see this as the only hope for the future protection of our coastal waters.

Postscript:

Paper presented on 17th April 2000 by Ken Macintyre, President of the Cottesloe Marine Protection Group inc. Community efforts in raising public awareness of the conservation value of the marine environment resulted in the Cottesloe Reef System being declared a Fish Habitat Protection Area (FHPA) in September 2001 by the Minister for Fisheries.