Psychic surgeons of the Western Desert

To the indigenous reader please be aware that this article may contain the names or images of persons who are deceased.

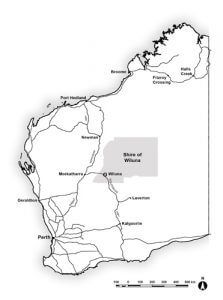

This paper was prepared by anthropologist Ken Macintyre, Toodyay, March 2007, based on observations and fieldnotes collected between 1973 and 1999 at Kalgoorlie and Wiluna.

Introduction

“Confidence between the healer and patient is more germane to treatment than the medicine itself.”(Imperato & Traore 1979:18)

The mapantjara or mapan is a traditional desert shaman of the Western Desert region, more popularly known today in Central Australia as ngangkari (healer or “clever man”). The knowledge of the mapantjara is in most cases inherited and passed down through the male line. However, in some instances an exceptional individual may become a mapantjara as a result of a revelatory dream or prophetic experience.

The mapantjara’s power to heal is grounded in a traditional knowledge of anatomy, physiology, manipulative massage and magic interwoven with a deep understanding of the esoteric ways of the creative totemic ancestors. The mapan’s powers of observation are acute. He is trained to look for the most subtle signs and indicators, not only in his client’s behaviour but in all aspects of his natural surroundings.

Spirit Familiars

A spirit or totemic familiar can be represented by almost any bird or animal. In the Western Desert, a powerful snake or sometimes a large lizard are the shaman’s (mapan) traditionally favoured choice of spirit assistant. The shaman’s familiar (often his totemic familiar) performs much of the difficult and magical tasks in the shamanistic healing ritual. When a mapan addresses his totemic familiar, he often uses the honorific kinship title of father.

Another type of spirit helper at the mapan’s disposal is a powerful host of small amorphous beings known as mapanpa. The term mapantjara means ‘he who has control of mapanpa.’ These tiny potent beings are believed to assist the healer to restore the life force to those suffering from a range of serious illnesses or, alternatively, to direct vengeance towards an offending party, whether supernatural or human.

Mapanpa are said to congregate in the mapan’s temple region, upper arms, and thighs and most abundantly in the abdomen (tjuni). They are pulled from the healer’s abdomen as required and inserted vigorously into the weakened parts of a client’s body to restore vitality and to drive alien magical and supernatural spirits out of the body.

To relieve the client’s anxiety and in some cases agitation, the mapan will massage areas of pressure points on the shoulder, neck and thorax to enhance his client’s breathing capacity (ngaanypa). Once the individual relaxes and his breathing becomes easier, he is more receptive to understanding his diagnosis and treatment as well as receiving positive suggestions towards recovery.

Psychic Surgery

When the illness is serious the mapan commands his client’s full attention during the massage ritual. This is especially the case when the mapan removes physical or sometimes invisible evidence of a malign agent known to have caused the particular disorder. This extractive ritual is a form of psychic surgery.

The shaman makes imperceptible incisions in the client’s body by digging his hands deeply into the soft pliable muscle tissue and then removing some culturally specific pathological material or object, such as dark coloured quartz crystals, a sharpened stone, bone or more commonly today invisible cord-like substances that are recognisable only to the healer. In Western desert culture these culturally-determined substances are believed to explain the aetiology of serious illness and suffering.

The origin of most life threatening disorders in traditional Australian Aboriginal society was attributed to sorcery or supernatural agents. I have witnessed contemporary mapantjara at Wiluna withdrawing what they describe as “virulent invisible substances” from their client’s bodies.

I could not help but notice the client wincing as the healer slowly withdrew the afflicting substance from his knee. This reaction is not uncommon. The feeling of an object or substance being psychically withdrawn from the body evokes in the client a physical sensation of extraction followed by release.

Patjala

The term patjala is a Western Desert term which literally means to bite. However, in this context it also refers to the deep sucking action of the mapantjara where he bites and sucks the affected part of a client’s body in order to remove painful blockages in the circulatory system. Dark coloured blood is extracted from the treated area and is spat, usually conspicuously, into a container or rag which is then shown to the patient and bystanders to provide evidence of the removal of the offending substance and cause of the malady. Blood obstructions are believed to be a cause of rheumatic pain, severe headaches and other ailments.

Patjala is generally used on those areas of the body that are soft and pliable and easily accessible, such as the neck, shoulders, lower back and knees. In all of the above procedures the mapantjara focuses his client’s attention on the importance of the ritual extraction of objects, whether visible or invisible, that are the culturally accepted agents of disease. Once the client is made aware that the source of his ailment has been removed, recovery is quick. The logic behind this traditional set of medical beliefs is that once a culturally determined cause has been diagnosed and removed by the mapan, the client must necessarily get better. It is for this reason that the offending substance is always shown to the client.

In the 1970’s when I first observed this ritual, I witnessed material objects such as pieces of quartz and bone being sucked and extracted from the affected parts of a client’s body. However, based on my observations in the mid-to-late 1990’s it would seem that the extraction of phlegmatic and magically contaminated blood and/or invisible cord-like substances are the currently accepted disease metaphors.

Throughout the ritual extraction of culturally-determined pathological substances, the mapan withdraws from his own abdomen the restoring life giving mapanpa and inserts them into the affected areas. This further reinforces the client’s belief in the powerful effects of the mapan’s treatment.

Throughout the healing process the mapantjara talks to his client in a relaxed manner, positively reassuring him and explaining the origin of his illness. The client’s knowledge of where his ailment originated empowers him to avoid dangerous situations in the future and to understand the shaman’s ritual of removing the cause of his malady. When the condition is complicated the mapan may take time to consider all the factors and consult with supernatural forces assisted by his spirit familiar. It is of utmost importance that the diagnosis is correct. Otherwise, the treatment ritual will not be successful.

This paper was prepared by anthropologist Ken Macintyre, Toodyay, March 2007, based on observations and fieldnotes collected between 1973 and 1999 at Kalgoorlie and Wiluna.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

For the purpose of this paper the term Western Desert refers to a cultural and linguistic bloc that identifies indigenous people with linguistic and cultural similarities who live in the arid and semi-arid regions of Central Australia. The mapantjara interviewed during my anthropological field work originally came from areas along the Canning Stock Route and Mangkalyi, Western Australia. They were residents at the Bondini Reserve in Wiluna.

I would like to thank the Aboriginal Lawmen from the Wiluna region including the Wongawol brothers, Mr Abbott, Mr Thompson, Mr Wheelbarrow – and most especially Mr Stevens from the transient fringe camp on the outskirts of Kalgoorlie who in 1973 introduced me to the healing practices of the mapantjara in Kalgoorlie. For many years he had been practising as a mapantjara traditional healer within the urban setting of Kalgoorlie. My first encounter with him was outside the Kalgoorlie Regional Hospital where he was treating two Elders from remote communities who were suffering from advanced cancer. Within two days of the men’s treatment which involved traditional massage and psychic surgical rituals, the two men were walking sprightly along Hannan Street, Kalgoorlie, looking for transport back to their respective communities. When I asked them how they felt, they replied that they had never felt better. We as Western observers should not underestimate the powers of the traditional mapantjara healers.

The Lawmen who participated in my anthropological research at Wiluna and Kalgoorlie all gave permission for me to use photographic and cultural materials obtained during these field visits. They all agreed that their medical treatments and traditions differed from those of Western-trained doctors but they had no doubts in the efficacy of their own culturally unique and ancient healing practices. The most vital ingredients of the mapantjara healing process is that the client must have a strong belief and certainty in the shaman’s ability to effect a cure. The mapantjara’s diagnosis is carefully explained to the client within a cultural context that gives meaning to the client’s pain and distress. Once both the client and the shaman have established the origin of the disorder, the practitioner then determines the most appropriate way to resolve his client’s distress and to bring him back to a state of wellbeing. It is interesting to note that in the Western Desert language the term for breath kurunpa also means spirit or soul.

The traditional cultural belief in the Western desert, which still survives to this day, is that illness is caused by revenge magic, supernatural agents or natural causes. Most treatments by mapantjara involve the removal and extinguishment of revengeful magical substances and malignant supernatural agents that enter the body often during sleep (Macintyre 1973 and 1993 unpublished fieldnotes). At no time does the client doubt the mapantjara’s ability to heal his ailment as the mapantjara’s reputation is well known to him.