Pre-contact indigenous Fremantle

Prepared by consulting anthropologists Ken Macintyre and Dr Barb Dobson for Fremantle Ports in February 2009. This summary is based on extensive archival research and field consultations originally carried out by Macintyre and Dobson in the 1990’s. Much of the information in the document below is based on this research.

Consultations were held between Noongar Elders and Fremantle Ports’ representatives in 2009. Numerous ideas were generated as a result of workshops facilitated by consulting anthropologists Ken Macintyre and Barb Dobson at Fremantle Ports. All the Elders agreed that a map of pre-contact indigenous Fremantle should be created which showed the original topographic and vegetation features of the Fremantle/ Swan River estuary region and showed Aboriginal heritage places of significance to traditional and contemporary Noongar people. The workshops involved representatives from nine different Noongar family groups. These included representatives from The Combined Swan River and Swan Coastal Plains and Darling Ranges Native Title Holders and Traditional Owners (CSR & SCP); the Independent Aboriginal Environmental Group (IAEG); The Bibbulman Tribal Group; the Ballaruk and Didjerak Peoples and the Whadjug Sovereign Group. The names of the individual participants are listed under acknowledgements at the end of this report.

This summary report details the outcome of the workshops carried out at Fremantle Ports in January and February 2009. It includes excerpts from earlier ethnohistorical and archival research of the Fremantle area carried out by Macintyre and Dobson in the 1990’s so as to provide the planners with a more thorough picture of indigenous Fremantle prior to European contact.

All Elders unanimously agreed that a map of pre-contact indigenous Fremantle would be the best way of highlighting to the wider population that Fremantle was a thriving indigenous community prior to white settlement and that its cultural significance continues to this day. They believed that the creation of such a map would not only be of great interest to tourists visiting the area but would provide an educational experience for all members of the wider community, indigenous and non-indigenous. The Elders believed that it would help to commemorate and provide recognition to the traditional inhabitants of the area and, most importantly, provide an important step towards reconciliation.

All were in agreement that a map of pre-contact Fremantle based on historical and ethnohistorical records and contemporary Elders’ input should incorporate the recommendations contained in this report and that it be installed in the Fremantle Port precinct at Victoria Quay to showcase Noongar culture as it used to be prior to European colonisation. The Elders suggested that the map be created in such a way as to depict the original topographic and vegetation features and to include traditional place names, indigenous habitation and food resource areas (fishing, hunting and gathering grounds); river crossing places and to highlight the traditional trading, ceremonial and mythological significance of the Fremantle and wider Swan River estuary area.

Interpretive map of pre-contact indigenous Fremantle – Part 1

Fremantle is traditionally located within Beeliar country, the boundaries of which are described by Lyon (1833) as follows:

‘Beeliar, the district of Midjegoorong, [also spelt Midgegooroo] is bounded by Melville water and the Canning, on the north; by the mountains on the east; by the sea on the west; and by a line, due east, from Mangles Bay, on the south. His headquarters are Mendyarrup, situated somewhere in Gaudoo [Candoo].’ (Lyon 1833 in Green 1979: 177)

Midjegoorong was the father of Yagan. The Elders were adamant that the map should include ethnohistorical information as well as indigenous heritage places along the Fremantle and Swan River estuary region. They wanted an educational and interpretive map of indigenous Fremantle to be prepared and installed at Victoria Quay as part of the larger proposed commercial development currently being planned (as of Feb 2009).

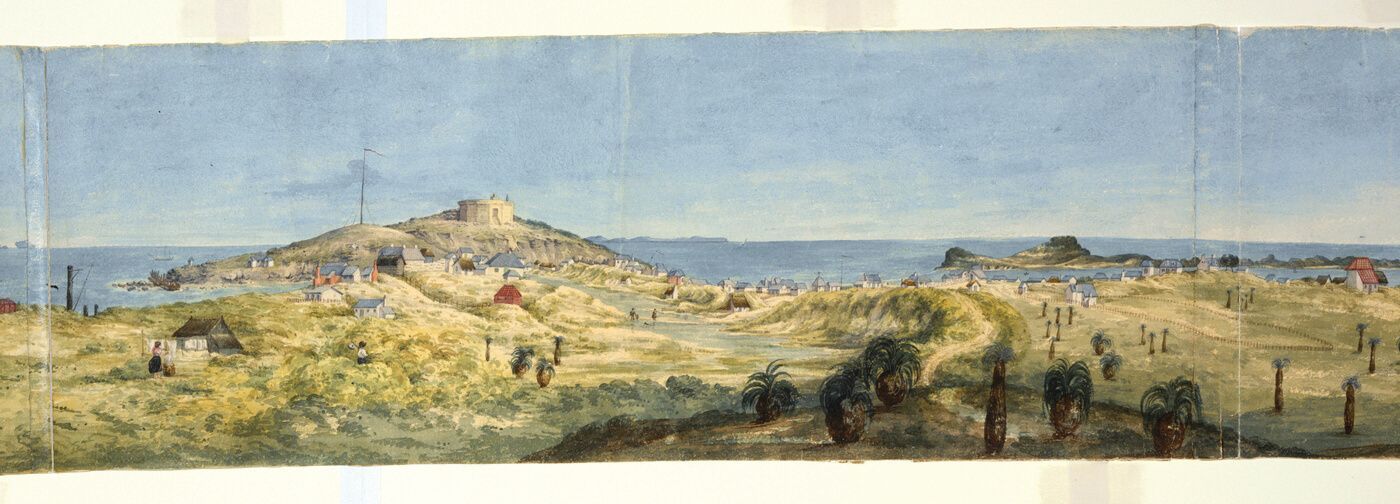

1. Topographic Features

It was recommended that the map show (a reconstruction of) the original topographic features of Fremantle area and the Swan River Estuary (known as “Derbal,” estuary or Derbal Yarragan, Swan River) as it would have looked prior to or at the time of European settlement. This map would depict the original geological and geographic features such as prominent limestone hills, ridges, cliffs, sand dunes, sand bars, shoals, swamps, original river shoreline, estuarine embayments and the rocky bar which used to exist across the entrance to the estuary. The map would show the coastal limestone belt known as Boyeembarra (Lyon 1833 in Green 1979:176) and the associated vegetation which was primarily Xanthorrhoea, limestone coastal heath, Acacia and Eucalyptus (for example, tuart).

Fremantle is located within the coastal limestone belt known in the Noongar language as Boyeembara. According to Robert Lyon (1833 in Green 1979: 176) “Boyeembara” refers to ‘the division along the coast, consisting principally of lime-stone rock; and generally bearing the xanthorea [sic], and a few of that species of the eucalyptus, called white gum. See booyee.’ [booyee, according to Lyon, means rock or stone p. 162]

Moore (1842) also makes reference to this coastal limestone belt under the entry ‘Bo-ye (stone, rock): ‘

‘The geological features of the country are not yet ascertained with any precision. The principal rocks are limestone, granite, basalt, and ironstone. The great strata appear to run nearly in a north and south direction. Next, and parallel to the sea coast, is a limestone district, with light sandy soil. Upon this are found the Tuart, the Mahogany [jarrah], and the Banksia.’

Stirling (1827 in Shoobert 2005: 32) refers to this same coastal limestone strip as:

‘The Limestone ridge of an average breadth of 3 Miles on the Sea Shore then the plain an undulating Valley of an average breadth of 30 Miles and lastly the mountain range rising abruptly from the plain to the height of 1200 feet and extending North and South on a line parallel with the Coast and apparently co-extensive with it.’

Seddon (2004: 242) provides a more recent description of the town of Fremantle:

‘bounded by water on two sides: South Bay on the south side, and North Bay at the mouth of the Swan River. To the east and west, it was sheltered by limestone ridges, Arthur Head to the west, with the Church Hill – Cantonment Hill ridge in the east.’

2. Traditional place names for Fremantle – Walyalup

The Elders recommended that the map should illustrate the original vegetation and topographic features of the Fremantle district and include traditional place names where these are known. Lyon (1833) records Walyalup as the name for Fremantle:

‘Walyalup, Fremantle; including both sides of the river, north and south’ (Lyon 1833 in Green 1979: 172)

The translated meaning of Walyalup is not provided by Lyon (1833). However we would suggest and this idea was supported by several senior Noongar Elders participating in the consultations with Fremantle Ports that the name Walyalup may derive its meaning from walyal (lungs) and up (place of) literally signifying ‘place of the lungs.’ Body part metaphors were often used when naming parts of rivers, headlands, hills and other prominent features of the landscape. Walyalup is probably an indigenous body part metaphor describing the simulated lung-like action of the alternating land and sea breezes which blew daily up and down the river with seasonal regularity, especially during summer and early autumn when Noongar people were camped in the riverine-estuarine coastal belt. The effects of these winds would have been most pronounced at the mouth of the Swan estuary close to where Fremantle is located. The rotating winds, alluded to in early historical accounts by Stirling (1827) and Von Huegel (1833) are described as follows:

Stirling (1827 in Shoobert 2005: 32) refers to ‘the alternate action of these two winds which seldom leave an intervening calm.’ He notes:

‘The hot Season of the day lasts but a few hours as the heat even then is mitigated by Sea breezes, and at night by the Land wind.’

When Baron Charles Von Huegel first arrived on the sandy soil at the mouth of the Swan River in Fremantle, Western Australia on 27 November 1833, he observed that

‘One feature of the fine weather in summer in Western Australia is that land and sea winds alternate. The land wind usually starts up at or just after sunrise and quickly rises to a gale. At about two or three o’clock, after a brief calm, the sea wind springs up and soon becomes so strong that hardly a boat will dare put to sea.’ (von Huegel 1833 in Clark 1994:33)

Little did Stirling (1827) and Von Huegel (1833) realise that what they were describing was an indigenous body part metaphor place name. Walyalup may also be interpreted as referring to the rhythmic ebb and flow of the tide as it moved across the rocky bar which in former times existed at the mouth of the Swan estuary. Stirling (in Shoobert 2005: 22 & 26) observed these tidal movements noting that ‘… the Tides on this Coast are very much influenced by the existing winds.’ The indigenous inhabitants were totally familiar with these wind and tide patterns which regulated their estuarine and coastal fishing activities.

Another example of an indigenous body part metaphor is “Derbal Nara.” Lyon describes Derbal Nara as:

‘the gulph of the Derbal. This comprehends Mangles Bay, Cockburn Sound, Owen’s Anchorage, Gages Roads, and the whole space from the main to the islands, and from Collie Head to the northern entrance beyond Rottenest’ (sic.) see Nara. See also Naral. (Lyon 1833 in Green 1979: 178).

Lyon records nara as meaning ‘the hollow of the hand’ and narall as meaning ‘the side’ (Lyon 1833) or according to Grey (1840) ‘the ribs’ (narra, narrail). It was pointed out to us by a Noongar Elder that Derbal Nara was a body part metaphor referring to the ‘hollow of the hand.’ He illustrated its meaning by cupping his hand to show how the hollow part represents the sea and the upper parts correspond to the higher contours of the mainland and islands. He said categorically that Derbal Nara refers to the place where the estuary (derbal) empties its flow into the sea.

3. Meeting place: Manjarup/ Mendyarrup/ Manjarip

It was requested that Noongar places names (where known) and their translated meanings (where possible) be included on the pre-contact Fremantle map.

Fremantle was also known as Manjarup (that is, manjar, ritual exchange + ‘up’ meaning “place of”). This is also rendered as Manjarip (Daisy Bates) or Mendyarrup (Lyon 1833) – the name of the “head-quarters” of Midgegooroo’s territory. This name, also popularly rendered as Manjaree, refers to the traditional meeting place that was located within the sheltered area to the east of the limestone ridge at Arthur’s Head and west of Cantonment Hill/Church Hill ridge – probably in the general location where the townsite of Fremantle is now situated.

Fremantle was traditionally located at the convergence of three major bidi or path ways: (i) the path to Fremantle from Mt Eliza which followed the north side of (and ran parallel to) the Swan River estuary. This was located in Mooroo country (the district of Yellagonga, northwards of Fremantle, ); (ii) the path to Fremantle from the Canning River area followed the south side of the river was located in Beeliar country (the leader Midgegooroo); and (iii) the path to Fremantle from the Murray River region located in Pinjarup [also Pinjareb] country (the leader Banyowla).

4. Habitation (camping grounds)

Bates (1929 in Bridge 1992: 3) refers to Wal’yulyup as:

‘the point near Fremantle old jetty’ which together with ‘Manjarip, the old Fremantle tunnel [near Arthur’s head] …were old camping places.’

Habitation areas were located in association with water sources, rivers, fresh water springs, soaks or digging wells. Springs and campsites referred to in historical sources for the Fremantle area include St Mary’s spring and a fresh water spring at Arthur’s Head. One of the Elders referred to a spring which comes out of the side of the hill at Preston Point (Niergarup). Others referred to springs at Blackwall Reach known as moan gabbi (black water). The track along both sides of Blackwall Reach is known as Jenalup (literally meaning “place of the foot” or foot path). Further research is needed to determine the approximate locations and names of other campsites and springs in the Fremantle region. A list of Noongar sites for the Fremantle area and Swan estuary region can be downloaded from the Department of Aboriginal Affairs website. See Appendix 1.

5. Food resources (fishing, hunting and gathering)

The Fremantle area was rich in food resources, most notably estuarine fish. The large shoals which dominated the estuary, which was protected for a large part of the year by a rocky bar and sand banks at its entrance, provided an abundant supply of fish that could easily be procured, largely through spearing.

Stirling (1827 in Shoobert 2005: 34) commented as early as 1827 that ‘they fish either with the Spear or Weirs planted in shoal places.’

The Swan River estuary people were known as Derbalang (which derives from derbal, estuary). Symmons (1842: vii, viii) translates this as meaning ‘of, or belonging to, the Estuary, particularly applied to the inhabitants on the banks.’ Lyon (1833) refers to their language as “Derbalese”.

The Noongar people of the Swan River estuary were noted for their extraordinary skills in spearing fish. A quote from the Western Australian (12th November 1831) referring to the Swan River natives points out that:

‘The accuracy with which they throw their spears is scarcely credible. Their mode of spearing fish has in it something by no means ungraceful, and the certainty with which they can strike even small fish at considerable distance in the water with a spear from fourteen to sixteen feet long, is astonishing….’

This long spear which never left the hand of the thrower was known as a gidgigarbel. Armstrong (1836) compares the local group on the Swan River with the northern groups and comments that:

‘Tribes to the north and north-east, who are far and confessedly superior to the Swan men in the ordinary use of the spear, are below comparison with the latter in fishing. Members of the former tribes have been standing by with the Interpreter, while a Swan man has been exercising this art; and the latter has not only seen but speared a fish, the very approach of which the former could not discover, though anxiously looking out for it. The quickness of their sight is well known to be astonishing – that of their hearing is scarcely less so.’

It would appear that the indigenous people of the Swan River Estuary consumed most species of fish. These included the yellow-finned whiting (mudu, murda), Perth herring (didi), tailor (margyn), sea mullet (kalkarda) and their all-year-round staple cobbler (karailya). In addition to the many different kinds of fish, there was an abundance of prawns and crabs at certain times of the year. The Noongar of the Perth region were terrified of sharks, especially the estuary bull shark. http://anthropologyfromtheshed.com/project/shark-in-nyungar-culture/

In addition to their diet of fish and estuarine waterfowl (ducks, swans and others), foods were also procured from the fresh water (or sometimes brackish) swamps and lagoons which dominated a considerable part of the pre-contact Fremantle landscape. Early maps show a line of swamps running parallel to South Bay. These swamp lands are illustrated in Jane Currie’s paintings in 1832. Typical swamp foods included gilgies, tortoises, mudfish and water fowl. Frogs (goya) were also a favoured source of protein. Animals hunted included possum, bandicoot, kangaroo, quokka, wallaby, emu, tamar, rats and lizards. Birds and birds eggs were a favoured part of the diet at certain times of the year. Insects and insect larvae, such as bardi, were also collected from the vast groves of Xanthorrhea which once dominated (what is now) the townsite of Fremantle. See our article on bardi farming and consumption http://anthropologyfromtheshed.com/project/the-bardi-grub-in-nyungar-culture/

According to early historical records, Drummond writing in 1839 at the Town of Fremantle, notes:

‘The spot where the town of Fremantle now stands was originally a grove of Xanthorrhoea [Xanthorrhoea preissii] called here Blackboys, but which now get scarce in the neighbourhood of settlements from the number used as firewood. The genus is of very slow growth, the largest specimens must be several hundred years old: these furnish the natives with a favourite article of food in the larvae of a large brown species of Cerambyx, and also afford a good substitute for lucifer matches.’

Root tubers and rhizomes also formed a substantial part of the coastal Noongar diet. These included the starch-rich seasonal staples of yanjet (Typha, bulrush), bohn (Haemodorum) and the tubers of certain lilies (kara) and orchids (djubak), the fruit and leaves of kolbogo (Carpobrotus, coastal pigface), the leaves of samphire which grew in the flat and sometimes salty swamplands along the estuary and other edible roots, fruits and seeds.

6. River crossings – “Matta Gerup”

It was established within the group workshops that the main river crossing was in the vicinity of what is marked on the old maps as Ferry Point, where a sandy promontory with lagoons and samphire flats/ reed vegetation (see old maps) extended out into the estuary leaving only a shallow channel of approximately one and a half feet deep which was “fordable” at certain times of the day. According to a 1841 hydrographic survey (chartered by Stokes on board the Beagle) this channel was a quarter of a fathom deep (equivalent to 1.5 feet) (see attached map).

“Matta Gerup” – It was suggested that the name of the river crossing or ford in the vicinity of Ferry Point was probably the same name as that recorded by Lyon (1833) which refers to a ford further upstream at Heirisson Island (where the Causeway is today) known as “Matta Gerup” (or more commonly known nowadays as “Matta Garup“). According to Lyon (1833) “The name seems to indicate that the water, at this celebrated ford, is only knee deep.’ (in Green 1979: 175). He further notes ‘…the shores of Melville water, where the water is, to a great extent on either side of the broad channel, not more than knee or thigh deep, it is admirably adapted to spear fishing…’ (in Green 1979: 175). It is interesting to note that Matta (which literally means “leg”) when used in this context may be viewed as an indigenous body part metaphor. It is likely that such a description would have applied to all shallow “fordable” or “knee deep” estuarine or river crossings.

It was suggested that the rocky bar and sand bar may have been used occasionally as a river crossing or for fishing but that this would have been dangerous at most times of the year.

7. Trading & ceremonial

The Elders recommended that important ceremonial places such as corroboree grounds and trading places (manjar) be depicted on the pre-contact Fremantle map. They stressed that the trading and ceremonial activities were inextricably bound together. Once could say that the main focus of manjar was ceremonial or ritual trading as many of the goods exchanged were for the production of weapons or ceremonial activities. All groups emphasised that Fremantle was the focus of an important regional trading centre long before white settlement.

Another aspect of the trading ceremony which was highlighted was that in order to support a large group of people for any length of time, there must be an abundance of food to feed them. It was suggested that the rich fishing grounds of the estuary (and even the protected coastal embayments) would have enabled this, especially at certain times of the year when schooling fish were abundant. The Elders were unsure as to the actual timing of the manjar; some suggested spring while others suggested late summer/autumn when the salmon or mullet were running.

Further research is needed to verify (as far as this is possible) the actual locations of the corroboree grounds, springs and campsites in the Fremantle area for the purposes of map accuracy.

8. Mythological: Dwerda (Dingo) totemic ancestor

All Elders pointed out that the Fremantle area was traditionally associated with the totemic Dingo Ancestor, known as dwerda (or doorda). This is reflected in the original Noongar name for Cantonment Hill which is Dwerda Weeardinup (also recorded as Dwerda Weelandinup) which is said to refer to the ‘place of the dingo spirit’ .

The whole extent of the Swan River, including the estuary and its mouth, is associated with Waugal mythology. Other areas which the Elders referred to as having mythological significance involving the Waugal included Garungup (limestone caves and surrounds at Rocky Bay, North Fremantle and Minim Cove, Mosman Park), Niergarup (Preston Point) and Anglesea Point (Walgoolup).

Garungup (Rocky Bay) was referred to as the place where the waugal got very angry and caused the great flood which separated the nearby islands of Rottnest and Carnac from the mainland. After doing this, the waugal then wrapped his tail around one of the pillars of the limestone cave and had a rest. This place name derives from the Noongar term garung (or its variants garang, karung, garrang etc) meaning angry, rage, vengeance or wroth.

Armstrong (1836 in Green 1979: 191) makes a passing reference to the waugal mythology in relation to explaining the separation of the mainland from the offshore islands; he simply notes (but unfortunately does not elaborate):

‘They state, as a fact handed down to them from their ancestors, that Garden Island was formerly united to the main [mainland], and that the separation was caused, in some preternatural manner, by the waugal.’

One Elder related how the rocky bar at the entrance to the Swan estuary represented part of the Waugal’s body after an enormous battle. Another Elder commented that the formation of the rocky bar made it a sheltered place for Noongars to fish, where they could see the bottom and could see sharks if they were in the vicinity.

The Noongar Elders recommended that the mythology associated with the Waugal (carpet snake) Dreaming and the Doorda (dwerda, dingo) Dreaming which both relate strongly to the Fremantle area should be presented in such a way that they can be artistically portrayed in a respectful, aesthetic and culturally approved manner on the proposed pre-contact indigenous Fremantle map.

Interpretive map of pre-contact indigenous Fremantle – Part 2

A second round of workshops were held on 9th February and 20th February 2009 where further ideas were generated regarding the pre-contact Fremantle map, and how it might be represented.

All groups once again expressed enthusiasm for the idea of a pre-contact map of the Fremantle/ Swan Estuary area (Macintyre and Dobson February 2009)

Some groups agreed that the map should be presented as a three dimensional wall scape in glass as this would make it look attractive and inviting to tourists as well as to the general community.

One group suggested that it could be made as a bronze casting. This would make it weather proof and vandal proof (especially if it was to be an outdoor installation). One Elder suggested that it could be done in bronze similar to the Kokoda Trail map which is located in Kings Park beside the War Memorial.

It was suggested that reproductions of this feature map could be installed (and/or made available to the public) at other locations within the Fremantle precinct, for those tourists visiting other parts of the city.

It was also recommended that the indigenous places and place names shown on the map should ideally correspond to plaques or markers throughout the Fremantle area which indicate the approximate locations of these old camp sites, corroborees, river crossing etc, so that those people who are interested can actually locate the significant places featured on the original feature map or wallscape. All parties agreed that this was a good idea. However, it was noted that such planning would need to work in with the City of Fremantle and the existing Fremantle Heritage Trail so that such signage complements, rather than duplicates, indigenous places of significance (which may already have been given cultural recognition on-the-ground).

Another (practical) idea was that the map scape could be placed horizontally rather than vertically, thus making it easier for the viewer to locate the features and places using the compass directions provided on the map.

A final meeting was held on Friday 20th February for those Elders who had been unable to make it to the earlier meeting. For their individual names, see under acknowledgments.

They were enthusiastic with the pre-contact map concept design which they had proposed in January 2009 and all agreed it would provide a wonderful showcase to tourists and the wider community alike as to what Fremantle was like in those times, and it would enable them to portray aspects of indigenous culture as it related to Fremantle at that time.

One Elder read out to Fremantle Ports’ representatives a list of native plants (together with some of their Noongar names) which would have featured in the coastal Fremantle area prior to contact. This was important from the point of view of Noongar traditional useage of these foods, medicines and resource materials (some are still used by Noongar families to this day).

One of the Elders emphasized that it was very important to make sure that the pre-contact Fremantle map in its depiction of the different aspects of Noongar culture does not represent Nyoongar culture as a fossilised relic which has no bearing on modern Noongars and their contemporary lives. He pointed out that although much of the original landscape has been destroyed, modified and changed, the Noongar people are nevertheless still “living” their culture and he wanted this message to somehow be incorporated into the design. It was agreed that this was a good point and that the notion of “continuity” of a ‘living’ culture must be recognised and highlighted.

Finally it should be emphasised that there was unanimous support and enthusiasm by all groups for a pre-contact Fremantle mapscape which would enable Noongar people to showcase some of the traditional aspects of their culture. They believed that this would serve as a drawcard for tourists and visitors to the Fremantle area.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

PART 1. JANUARY 2009 MEETINGS WITH THE NOONGAR ELDERS

SUMMARY OF IDEAS GENERATED AT WORKSHOPS HELD AT FREMANTLE PORTS ON 28TH JANUARY 2009 WITH SENIOR REPRESENTATIVES FROM THE WILKES, BROPHO, CORUNNA, GARLETT, WARRELL, HUME, COLBUNG, BODNEY AND JACOBS FAMILIES (without Fremantle Ports representatives being present)

3 SEPARATE MEETINGS – WEDNESDAY 28TH JANUARY

MEETING 1 – Members of The Combined Swan River and Swan Coastal Plains and Darling Ranges Native Title Holders and Traditional Owners (CSR & SCP)

Richard & Olive Wilkes; Albert & Gwen Corunna; Greg Garlett & Dulcie Donaldson;Victor Warrell & Hayley Warrell; Bella Bropho

MEETING 2 – Senior representatives of the Independent Aboriginal Environmental Group (IAEG) Patrick Hume & Rebecca Hume; The Bibbulman Tribal Group representatives – Phil Prosser & Esandra Colbung; and the senior most representative of the Ballaruk and Didjerak Peoples Corrie Bodney & Melba Bodney

MEETING 3 – Cedric Jacobs & Kezia Jacobs-Smith (Whadjug Sovereign Group) representatives

PART 2 – February 2009 MEETINGS WITH NOONGAR ELDERS

Meetings were held with these same Noongar family groups (as above) and senior Fremantle Ports representatives, Ainslie de Vos, Dean Davidson, Jeanette Murphy and Franco Andreoni on Monday 9th February (and Friday 20 February) in the presence of consulting anthropologists Macintyre and Dobson to enable the Elders to present their views to Fremantle Ports representatives regarding their proposed Pre- Contact Fremantle Map which they had suggested at a previous meeting (in January 2009). At these meetings all groups expressed enthusiasm for the idea of a pre- contact map of the Fremantle/ Swan Estuary area.

Monday 9th February

Meeting 1

A meeting was held with Aboriginal consultants Richard Wilkes, Olive Wilkes, Bella Bropho, William (‘Toopy’) Bodney, Victor Warrell and Justin Warrell, together with senior Fremantle Ports representatives Ainslie de Vos, Dean Davidson, Jeanette Murray and Franco Andreoni, in the presence of consulting anthropologists Ken Macintyre and Dr Barb Dobson from Macintyre Dobson and Associates Pty Ltd.

Meeting 2

A meeting was held with Aboriginal consultants Patrick Hume, Rebecca Hume, Corrie Bodney, Melba Bodney, and Phil Prosser, together with senior Fremantle Ports representatives Ainslie de Vos, Dean Davidson, and Jeanette Murray in the presence of consulting anthropologists Ken Macintyre and Dr Barb Dobson from Macintyre Dobson and Associates Pty Ltd.

Meeting 3

A meeting was held with Aboriginal consultants Cedric Jacobs and Kezia Jacobs- Smith together with senior Fremantle Ports representatives Ainslie de Vos and Jeanette Murray in the presence of consulting anthropologists Ken Macintyre and Dr Barb Dobson from Macintyre Dobson and Associates Pty Ltd.

BIBILOGRAPHY

Appleyard,S.J., Macintyre, K. and B. Dobson 2001 “Protecting ‘Living Water ‘: involving Western Australian Aboriginal communities in the management of groundwater quality issues”. Paper presented at the International Groundwater Management Conference, University of Sheffield, England. April.

Armstrong, F. (Interpreter) 1836 ‘Manners and Habits of the Aborigines of Western Australia, from information collected by Mr. F. Armstrong, Interpreter. Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal. Volume XX. 5th November.

Bates, D. 1952 The Passing of the Aborigines. : A Lifetime spent among the Natives of Australia. London: John Murray.

Bindon, P. and Chadwick,R. 1992 A Nyoongar Wordlist from the south-west of Western Australia. Perth: Anthropology Department, W.A. Museum.

Bridge,P. (ed.) 1992 Aboriginal Perth: Bibbulmun Biographies and Legends by Daisy Bates. Victoria Park: Hesperian Press.

Bropho, Robert 1980 Fringedweller. Sydney: Alternative Publishing Cooperative Limited.

Christie, M.J. 1991 Aboriginal Science for an Ecologically Sustainable Future, Australian Teachers Journal, March.

Curr, E. 1886 The Australian Race: its origins, languages, customs, place of landing in Australia, and the routes by which it spread itself over that continent. Melbourne: Government Print.

Drummond, James 1839. Letter to Sir W.J. Hooker. Extracted from the Journal of Botany (Hooker’s Journal of Botany). Vol. II. Drummond’s letter was written from the Town of Fremantle, Swan River Colony, June 1839.

Green, N. (ed.) 1979 Nyungar-The People: Aboriginal customs of the southwest of Australia. Perth: Creative Research.

Green, N. 1984 Broken Spears: Aboriginals and Europeans in the southwest of Australia. Cottesloe: Focus Education Services.

Green, N. and Moon, S. 1997 Far from Home: Aboriginal Prisoners of Rottnest Island 1838 1931 Dictionary of Western Australians, Vol X. Perth: University of WA Press.

Grey, G. 1840 A Vocabulary of the Dialects of South Western Australia. London: T & W Boone.

Haebich, A. 1988 For Their Own Good: Aborigines and Government in the Southwest of Western Australia, 1900-1940. Nedlands: University of WA Press.

Hallam, S. J. 1975 Fire and Hearth: a study of Aboriginal usage and European usurpation in south-western Australia. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

Hallam, S. and Tilbrook, L. 1990 Aborigines of the Southwest Region 1829-1840. The Bicentennial Dictionary of Western Australia. Nedlands: University of WA Press.

Lyon, R.M. 1833 ‘A Glance at the Manners, and Language of the Aboriginal Inhabitants of Western Australia; with a short vocabulary.’ 23 March. In N.Green (ed.) 1979 Nyungar – The People: Aboriginal customs in the southwest of Australia. Perth: Creative Research.

Macintyre, K. and B. Dobson (1999) ‘Factoring Aboriginal Environmental Values in Major Planning Projects.’ Australian Environmental Law News, Issue No. 2 June/July.

Macintyre, Ken 2000 ‘Generating Community Awareness of the Cottesloe Reef System: An Anthropological Perspective.’ Paper presented at the Annual MESA Conference, Fremantle: Notre Dame University. April.

Macintyre Dobson and Associates Pty Ltd and T.O’Reilly 2002 Report on an Ethnographic, Ethnohistorical, Archaeological and Indigenous Environmental Survey of the Underwood Avenue Bushland Project Area, Shenton Park. Prepared for the University of Western Australia. June. Unpublished report.

Macintyre Dobson and Associates Pty Ltd (2004) Aboriginal Habitation and Usage of the Swan River and Swan Coastal Plain. Unpublished Manuscript.

Macintyre, Ken 2004 Aborigines and the Cottesloe Coast. Paper presented at the Cottesloe Fish Habitat Protection Area Seminar sponsored by Coastcare. May

Macintyre, K. and B. Dobson 2008 Nyungar places of significance along the Swan River Estuary. Unpublished paper.

Moore, G.F. 1842 A Descriptive Vocabulary of the Language in Common Use Amongst the Aborigines of Western Australia. London: William S.Orr.

Moore, G.F. 1884 A descriptive vocabulary of the language in common use amongst the Aborigines of Western Australia. 2nd ed. Sydney: G.F. Moore

Moore, G.F. 1984 [1884] Diary of Ten Years of an Early Settler in Western Australia. Perth: University of Western Australia Press.

O’Connor,R.; Bodney,C. and Little,L. (1985) Preliminary report on the Survey of Aboriginal Areas of Significance in the Perth Metropolitan and Murray River Regions. Unpublished. July.

O’Connor, R.; Quartermaine, G. and Bodney, C. 1989 Report on an Investigation into Aboriginal Significance of Wetlands and Rivers in the Perth-Bunbury Region. Leederville: Western Australian Water Resources Council.

Shoobert J. 2005 Western Australian Exploration 1826-1835, The Letters, Reports & Journals of Exploration and Discovery in Western Australia. Vol 1. Victoria Park: Hesperian Press.

Stirling, J. 1827 Diary. Expedition up the Swan River in 1826. Perth: Battye Library Collection.

Tilbrook, L. 1983 Nyungar Tradition: Glimpses of Aborigines of South-Western Australia 1829-1914. Nedlands: University of Western Australia.

Weaver, P. R. 1997 Marine Resource Exploitation in South Western Australia prior to 1901. Unpublished Ph D Thesis, Edith Cowan University.

White, I. (ed.) 1985 Daisy Bates: The Native Tribes of Western Australia. Canberra: National Library of Australia.

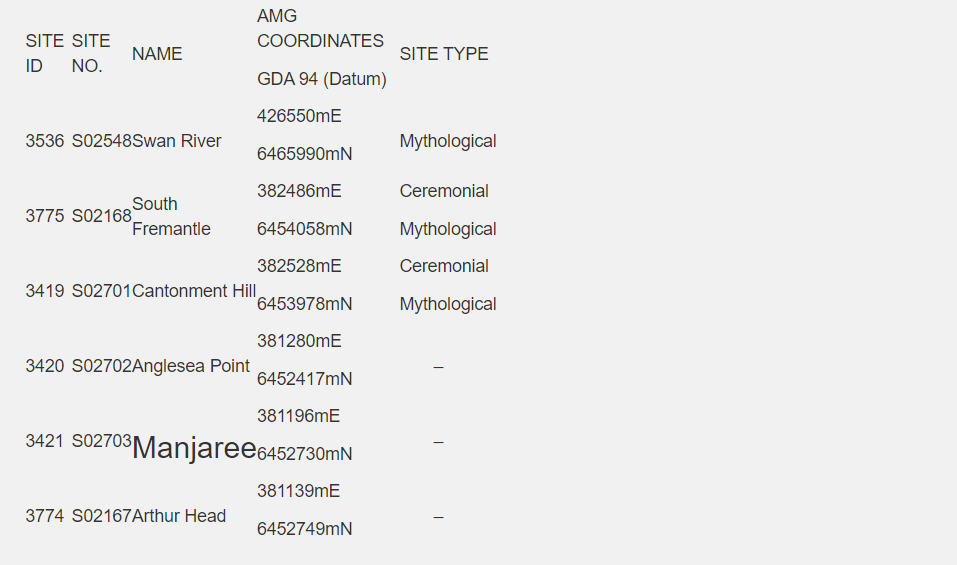

APPENDIX 1: Appendix - Aboriginal sites in the Fremantle area (registered at DIA 2004)

The site information below derives from our report:

Macintyre Dobson and Associates Pty Ltd 2004 Report on an Ethnographic Survey of the Proposed Fremantle Inner Harbour Dredging Project Area. Prepared for Fremantle Ports. November. Meetings and Consultations carried out by consulting anthropologists Ken Macintyre and Dr Barbara Dobson

On page 9 it states:

6.2 Previously Recorded Sites

According to the Register of Aboriginal Sites at the Department of Indigenous Affairs (DIA) there are six previously recorded sites of Aboriginal significance located in the vicinity of Fremantle (see Table 1 below and Appendix 9.2). However, there is only one site – the Swan River (S02548) – which will be impacted by the proposed dredging programme. The Swan River estuary was first recorded by Lyons (1833) as the Derbal Yaragan (Derbal meaning ‘the name of the country surrounding the river’ and Yaragan meaning ‘river’, see Green 1979). To this day indigenous consultants still use the name Derbal Yaragan to refer to the Swan River .

It is also interesting to note that Lyons (1833) refers to Derbal Nara (the gulph of the Derbal) as encompassing “Mangles Bay, Cockburn Sound, Owen’s Anchorage, Gages Roads, and the whole space from the main to the islands, and from Collie Head to the northern entrance, beyond Rottenest (sic).” (in Green 1979:178). Nara here refers to ‘the hollow or hand’ of Derbal, the name of the country. Derbal Nara refers to the continuation of the river estuary out into the sea.

The mythological significance of the Swan River is attributed to the Waugal (or Wagyle), an ancestral creative snake-like being, or as it is sometimes called the Rainbow Serpent.

Table 1: Previously Recorded Sites of Aboriginal Significance in the Vicinity of Fremantle (Source: DIA Register of Aboriginal Sites, November 2004