Indigenous significance of Mudurup Rocks, Cottesloe

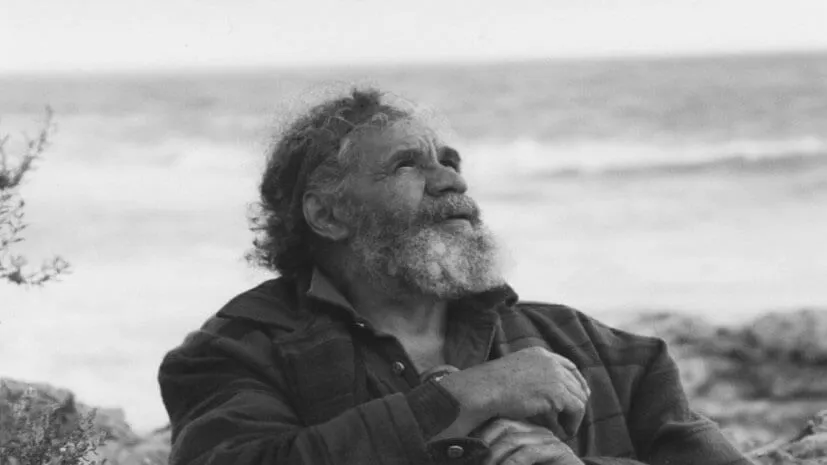

Ken Macintyre and Dr Barb Dobson

Overview

This paper is based on research compiled over the past twenty-five years by consulting anthropologists Ken Macintyre and Dr Barb Dobson. The information derives from both ethnohistorical sources and narratives collected from contemporary Nyungar Elders. We would like to thank all Nyungar Elders (past and present) who over the years have assisted us by providing cultural information without which this paper would not have been possible.

To traditional Nyungar people ‘Kadjil the Crow man’ was believed to possess the powerful magic of a sorcerer (bulyagaduk) and is said to have had the ability to transform himself from a man into a crow. Indigenous oral history states that Mudurup (or coastal Cottesloe) was one of the traditional haunts (or in Nyungar terms the ’run’) of the crow or warrdung.1

In traditional belief crows were the messengers of the rain beings, thunder beings and the wind. Only a powerful sorcerer, such as the Crow man, could divine the subtle unpredictability of these natural elements. When storms approached, the Crow man would announce its coming to his kinsmen, the loud screeching oolynark (white-tailed black cockatoo) and excite the busy movements of the biddit (ants). These would indicate to Aboriginal people the coming of stormy weather (Bodney personal communication 1993).

Bodney stated that it was said by ‘the old people’ that when the warrdung who had their camp on Rottnest Island (Wajemup) visited the coast at Mudurup, they would herald the arrival of the mullet (Mugil cephalus) and salmon (Arripis truttacea). This was a sign of a time of plenty. Even in traditional times when Aboriginal people moved inland in late autumn/early winter to escape the onset of the harsh wintry conditions on the coast, they knew that the Crow man would continue his weather forecasts through his obliging kin, the black cockatoo and the ants.

Mudurup Rocks

Mudurup Rocks is one of the last known and surviving indigenous mythological, ceremonial and fishing sites located on the Western Australian metropolitan coast. It is registered as Site ID 435 at the Department of Aboriginal Affairs, Cultural and Heritage Division, Perth. According to site file information recorded in 1995 ‘the site is located immediately W. of the Cottesloe Surf Lifesaving Club and SSE of the Cottesloe Beach Groyne.’ However, based on our own consultations over a number of years with senior indigenous heritage spokespersons with knowledge of the area, the site originally extended north and south of the present day groyne. It is said to have included part of the rocky shoreline and beachfront limestone formations which existed there prior to the construction of the groyne (see Figure 3). As the northern area has been changed and disturbed over many years, the site extent now seems to have been conveniently confined to the south of the main groyne.

The original site name Mudurup (pronounced ‘Moordoorup’ or ‘Murdarup’) which means ‘place of whiting’ derives from the Nyungar mudu (or muda, murdar, murda or muda) meaning whiting + up, meaning place of. 4 In the context of Cottesloe it is said to refer to the place of the yellowfinned whiting (or yellowfin whiting) — this being the species (Sillago schomburgkii) most commonly found in this area. This species (see Figure 2), also commonly known as the Western Sand Whiting is, according to Hutchins and Thompson (1983: 34) ‘Abundant on sandy bottoms in shallow coastal areas.’ Hyndes and Potter (1997: 435) note that this species ‘spends its entire life cycle’ in ‘sheltered nearshore waters in southwestern Australia’ where it ‘spawns predominantly from December to February.’ We would suggest that the whiting’s breeding cycle was a dependable seasonal marker which drew Nyungar people to the coast at this time to take advantage of this abundant food source.

One senior Aboriginal consultant (Bodney) was convinced that Mudurup was the district name prior to white settlement. He suggested that Mudurup Rocks was an Anglicised adaptation of the original name Mudurup. All senior Aboriginal spokespersons who visited Mudurup Rocks with us over the years between 1993 and 2001 concluded that the site included the limestone headland or promontory (to the west of the Cottesloe Surf Club building), the fringing reef platform and the rocky beachfront area which once extended north and south of the present day groyne (see Figures 3 & 4). The construction of the groyne in the early 1960’s altered aspects of the shoreline and reef topography of the original site.

Consultants were unanimous that the Mudurup Rocks site included all the high ground, including the ground on which the surf club is built. Two Elders, Humphries (1992) and Colbung (1998, 1999, 2000) were convinced that the site extended northwards beyond the sloping ground on which the Indiana Teahouse is now located. Since the turn of the century there has been a history of building on the high ground at Mudurup Rocks. These buildings have included a skating rink, a cinema and assortment of wooden structures which served as changerooms for bathers (see Appendix: Figures 14 & 15)

One reason why the boundaries of Mudurup could not be clearly established was that traditional districts and defined places were typically frequented by different family groups, often to the extent that locality names simply morphed into other districts and named places. From our experience it is not uncommon for Aboriginal place names to denote a broader area than a particular feature which may indeed be the focal point of a totemic ceremonial area.

Bodney (1993) remembers ‘the old people’ referring to the Cottesloe coastal area as Mudurup. He believed the rocky promontory known as Mudurup Rocks was an important cultural heritage place within the general area known by traditional people as Mudurup. He recalled being told by an elderly uncle who camped at Swanbourne that the “Mobyne Crowman Cudgill” camped at Mudurup Rocks where he performed “sacred spiritual” rituals. He said that these ceremonies helped to reassure the ‘old people’ that their ancestors were still “watching out for them.” Bodney further stated that only special people with knowledge of the Law would have frequented the mysterious caves and cliffs on the rocks. The ‘old people’ told him that there were once caverns that reached deep under the sea where dark and mysterious rituals were performed. He was told by his mother and some other elderly Nyungars that the white people were frightened of these places and blew them up with dynamite. Indeed such an incident did occur in the 1930’s when the caves at Mudurup Rocks were blasted by local government authorities in the name of public safety (The West Australian 1937). Even to this day the weathered limestone overhangs at Mudurup Rocks are still a constant safety concern to the Town of Cottesloe (see Figure 5).

In an interview with Dame Rachel Cleland in 1999 she vividly recalled the caves that were located in the limestone rocks at Mudurup in the 1920’s. She said that she used to visit and play on Mudurup Rocks when she was a child about eight or nine years of age. She remembered one prominent cave, known by the children as ‘the pirates’ cave,’ which she described as having stalactite structures on the upper part of the cave entrance. She said they looked like teeth. She recounted how someone had told her that Mudurup was an important place to the local Aboriginal group and she remembered them fishing there (personal communication 1999).

Bodney (1995) further speculated that the caves at Mudurup may have had something to do with increase ceremonies to ensure a plentiful supply of whiting.5 He said that

‘the old people must have negotiated through ceremonies with the spirit that controlled the supply of the mudar. This spirit was the gobourn (totem) of the old people who performed the sacred rituals. They were the custodians of this place.’

Bodney (1995) pointed out from the high ground where we were standing (just west of the Cottesloe Surf Club) that this area would have been used in traditional times as a ‘look out’ to spot large schools of migratory fish, such as whiting, mullet, salmon, tailor, mulloway and schnapper. He recalled how as a boy in the 1940’s and 1950’s he himself had speared whiting with his brothers at Cottesloe using home-made gidgees made from a prong of thick fencing wire on the end of a broom handle. He said: ’We always brought back a good feed for our family.’ Whiting were an important and reliable in-shore sandbank food source during summer and early autumn.6

Ken Colbung had a different view on the ceremonial significance of Mudurup Rocks. He told us that he had already recorded the mythology of the site with Pat Vinnicombe from the DAA as involving moonder the tiger shark and he believed that the area was traditionally known as Moonderup rather than Mudurup. Colbung, in his reading of the weathered limestone promontory, said that he came to the conclusion that a cave entrance, rocky overhang with fractured stalactite-like structures and eroded limestone features symbolised to him the head, mouth and teeth of a large shark. It was for this reason that he believed the place was misnamed and should have been called Moonderup, meaning ‘place of the shark.’ We could find no historical or ethnographic reference to Mudurup Rocks as Moonderup in the archival literature. Old newspaper reports showed that the name Mudurup Rocks had always applied, ever since the time of settlement of Cottesloe in the 1890’s.

The Department of Aboriginal Affairs changed the name of the site from Mudurup to Moonderup based on the site information provided by Ken Colbung and recorded by archaeologist Pat Vinnicombe from DAA in 1995. We believe that this is a very flimsy basis for a historic name change, especially when all the other Aboriginal heritage spokespersons (including Cliff Humphries 1992 and Corrie Bodney 1994, 1995) had stated categorically that the place had always been known to them as Mudurup, and as far back as they could recall all the ‘old people’ had called it Mudurup (pronounced Moordorup). They had no knowledge of Mudurup Rocks being associated with shark mythology. However, they were aware of a place called Moondarup (or Moonderup) which they believed was located further south along the coastline, extending towards the old Cable Station at South Cottesloe/ Mosman Park where there were ancient limestone formations. Ken Colbung agreed that all these limestone features were associated with the Shark Dreaming.

Over and above Mudurup Rocks being viewed by Ken Colbung as the totemic place of the shark, he also described its connection to other sites such as Karbomunup (Loretto Convent, Claremont Hill S02145), emphasising its importance as a teaching site for initiates. The DAA site file states:

‘Initiates were taken to Moonderup and taught about Kurannup, the destination of the spirits of the dead beyond the western sea (see also Daisy Bates, The Passing of the Aborigines, 1966: 60). It was believed that the spirits followed the setting sun, and from Moonderup there is a clear view of the setting sun which drops below the horizon between Garden Island and Rottnest Island which is also associated with the spirits of the dead.’ (1995, K. Colbung & P. Vinnicombe)

While there were differences of opinion among Nyungar heritage spokespersons consulted between 1992 and 2001 as to the mythological narrative and symbolism associated with Mudurup Rocks, all agreed that it was a place of deep spiritual, ceremonial and ancestral importance. When in a group consultation with several Elders, including Ken Colbung, we visited a place called by the Elders Moondarup (or Moonderup) which was several kilometres to the south of Mudurup Rocks, south of the Beach Street groyne towards the old Cable Station. It was a place of remnant limestone rocks, caves and cliffs. The Elders agreed that the place name Moondarup meant ‘place of the shark’ but they could not agree on which type. Colbung emphasised that the Bibbulmen people had always associated “Moonderup” with the totemic mythology of the shark and he suggested that the shark in question was the tiger shark. We asked the Elders whether moonda (or moonder) could have denoted the Port Jackson (Heterodontus portusjacksoni) or the wobbegong (Orectolobus species) these being the two most commonly found sharks on the inshore reef system at Cottesloe but no one could say (see Figures 7 & 8).7

The above two photos were taken by members of the Western Australian Underwater Photographic Society (WAUPS) on the Cottesloe Reefs as part of a photographic competition and display at the Seadragon Festival in 2000 on Cottesloe Beach. The purpose of the annual Seadragon Festival was to promote public awareness and protection of the unique biodiversity of the marine environment at the Cottesloe reefs. Extensive community campaigning and government lobbying by the Cottesloe Marine Protection Group Inc. from 1999 to 2001 led to the successful establishment of a Fish Habitat Protection Area in September 2001.8

The meaning of moon-do according to Grey (1840: 87) is ‘a species of shark, which the natives do not eat.’ Moore (1842: 57) records mundo as ‘Squalus; the shark ’ and also notes ‘The natives do not eat this fish.’ Neither recorder attributes mundo to a named species.9 Early ethnohistorical sources from the Albany region also point out that the Nyungar did not eat shark or stingray flesh.10 See our paper http://anthropologyfromtheshed.com/project/shark-in-nyungar-culture/

While inspecting the shoreline at Moondarup, Ken Colbung showed us two natural limestone structures (still extant about 100 meters south of the Beach Street Groyne) which he stated were once part of the Moondarup ceremonial site. One of these was a single hollow natural limestone formation, the top of which was cemented with fossiliferous material (see Figure 9). The hollow stone structure had a small opening to the north and a larger opening to the south. About 25 meters further south along the beach were the eroded remains of another limestone formation. Colbung (1999) believed that both of these hollow stone formations would have once been used for mythological and ceremonial rituals known only to traditional Lawmen.

Archaeological Evidence of Aboriginal Habitation

Some of the Elders consulted were aware of ancient Nyungar campsites which had been located by archaeologists in the 1960’s and 1970’s in the Cottesloe/ Mosman Park coastal belt. These indicated a long history of seasonal occupation of this coastal area. Two of the sites registered at the Department of Aboriginal Affairs are Site ID 3335 (Victoria Street Station) and site ID 3336 (MacArthur Street, Mosman Park). These are no longer considered sites of significance under DAA site registration procedures. Other isolated artefacts have been located in the sand dunes near fringing vegetation in the vicinity of Vlamingh Memorial and the old Cable Station. These include pre-contact and post-contact materials. Isolated fragments of worked bottle glass prove that these pre-contact sites were occupied into post-colonial times (see Figures 10 and 11).

Bodney (1993) stated that coastal Aboriginal people traditionally collected fresh water from natural springs located in the sand dunes and limestone formations. However, he did not have any information as to the exact location of the water source in this particular location along the coast. One natural spring was found on the north side of the Beach Street Groyne (which is also known as the Dutch Inn Groyne), almost at the same location as an existing storm water drain. This area seems to be an underground discharge area for fresh water (see Figure 12).

Bodney (1994) further explained that fresh water may have been collected from the surface of the ocean where it was discharged from the aquifer as underground streams in the limestone reefs. He said that it is easily located as it looks like a long, oily slick. This oily impression is caused by iron molecules suspended in the fresh water which, being lighter than the heavier seawater, floats on top. He suggested that fresh water could have been easily scooped from the surface in earlier times using paper bark containers, when other sources of fresh water were depleted. Bodney and Colbung both believed that these streams of fresh water were the spiritual manifestations of the Waugal and that they symbolised the inter-connectivity between the terrestrial Waugal and the sea Waugal. Nyungar cosmology traditionally recognises an inter-connectivity between all facets of the natural environment. Within their world view it is not impossible for them to perceive humans and animals as being one. It is even possible for them to believe that humans could transform themselves into other animal and bird forms and that these animal and bird forms could also assume the guise of humans. Such beliefs form an integral part of traditional Nyungar Dreaming mythology.

And now let us get back to the story of Kadjil, the Crowman. There is no doubt that the story of the Crow man has its origin in ancient Nyungar tradition. However, the story of Cudgel (whose name may also be rendered as Cudgell, Cadjil, Kudgel, Kudjil, Kadjil or Kutjil) is another story, a more contemporary one involving a real life character by the name of Johnny Cudgel.11 In traditional mythology the warrdung (crow) sometimes assumed the role of a wise man, a cunning trickster or a malicious “bulya man” or sorcerer. Cudgel was all three. Some high ranking sorcerers were believed to metamorphose into birds, such as crows and owls, and to travel great distances in such guise to seek out their unsuspecting victims. There was no escaping the crow man unless the crow man was a clever bulya man persecuted by an enemy tribe, as in the story of Johnny Cudgel.

Cudgel was a perennial gaol bird, a hero to Nyungar people, who flouted white authority whenever possible, especially when it involved matters of inequity and injustice between black and white people of southwestern Australia. Johnny Cudgel was a regular inmate of the Rottnest Island gaol between 1890 and 1925.

In 1892 at the age of 18 Cudgel received heroic newspaper coverage of his daring escape during a violent storm from the lighthouse on Breaksea Island off the coast of Albany where he had been billeted on work duties. By the early part of the 20th century Cudgel had become a media star, a black bush ranger and a folk hero to the oppressed Nyungar people of southwestern Australia. Stories of his uncanny ability to escape from the custody of Her Majesty’s gaols abounded within the community to the point where his feats became seen as superhuman, not to mention his perceived ability to transform himself into a crow and mysteriously escape across the sea from the notorious Rottnest Island prison.

Nyungar Elders who had formerly camped at the Swanbourne site (where the new Swanbourne Primary School now stands) remembered stories told to them by ‘the old people’ around the fire at night about Kadjil’s miraculous escape from Rottnest Island. There was no doubt in their minds that this story was true and that Johnny Kadjil (or Cudgel) had indeed landed in the semblance of a crow on a beach not far from the (then) Swanbourne camp.12 In another version of the story we find him as the Crow man camped in a cave at Mudurup Rocks performing sacred ceremonies. We could find no documented evidence of Cudgel’s escape from Rottnest. However, the Swanbourne fringe camp-dwellers and their descendants were (and still are) convinced by the oral history passed down to them that Kadjil’s spirit had escaped and visited his people in the guise of a crow. By the 1920’s Cudgel had become a legendary character of Nyungar folk mythology. It is not difficult to imagine how such a powerful contemporary folk hero as Cudgel rejuvenated the traditional narrative of what is now known as ‘Kadjil, the crow man.’

ANNOTATIONS

- Nyungar names and terms (such as Kadjil, warrdung, bulya, bulya-gadak and even the term Nyungar itself) can be rendered in many different ways. There is no single ‘correct’ spelling as the Nyungar language is traditionally an oral one. Choice of spelling usually depends on an individual or group’s preferred orthography and/or regional or dialectical linguistic variations.The term Nyungar which denotes Aboriginal people whose roots traditionally derive from southwestern Australia, can be spelt Nyoongar, Noongar or Nyungah, depending on individual or group preferences. The language is fundamentally similar throughout southwestern Australia (as noted by Grey 1840, Moore 1842, Bates 1914 and others) albeit with regional and dialectical variations (and in some cases colloquial terms and expressions which are confined to a particular district).The term bulya or bulya-gadak (also boylya or boylya-gadak) used in this paper refers to a shaman or sorcerer reputed to possess great powers to both heal and destroy. Grey (1840: 17) records boylya as ‘a sorcerer, the buck-witch of Scotland, a certain power of witchcraft’ and boylya gaduk as ‘one possessing the power of boylya.’ Moore in his Descriptive Vocabulary describes boylya gadak as: ‘One possessed of Boylya; a wizard; magician. The men only are believed to possess this power. A person thus endowed can transport himself through the air at pleasure, being invisible to every one but his fellowBoylyagadak…’ (Moore 1842: 13)It was believed that bulya men had the power to fly, often in the guise of a familiar bird, such as a crow or owl, thereby becoming known in mythology as the ‘crow-man’ or ‘owlman’. Some shamanistic practitioners were known as mulga-gadak (mulgar, thunder + gadak, having or possessing). They were said to control such natural phenomena as thunder and lightning, such were their perceived powers. In traditional culture most illnesses and unexplained deaths were attributed to the practice of sorcery.

- The crow (or “Australian Raven” as it is properly called) is known as wardong (which can also be spelt wardang, woodung, wardung, warrdung, worrdung or wordung). The etymology of the name is unknown. We would speculate that it may be a descriptor name which refers to wardo (“throat”), this being a reference to the bird’s distinctive throat feathers or hackles which become extended when calling. Nyungar bird names traditionally reflected distinctive physical characteristics, habitat, behaviours or calls which facilitated their identification.The crow had an enormous cultural significance in traditional Nyungar culture. It was an important totemic symbol in the traditional moiety system which divided society into two “halves.” These moieties were known as Wordungmat or the crow moiety (deriving from wordung, crow + mat, ‘leg’ or ‘family’) and Manichmat, the white cockatoo moiety (deriving from manich or munitch meaning white cockatoo + mat, ‘leg’ or ‘family’). Moiety marriage rules stipulated that a wordungmat (member of the crow family) must marry a manichmat (member of the white cockatoo family) or vice versa. It was forbidden to marry within one’s own moiety.Each moiety was named after a powerful Ancestral Dreaming spirit. The crow after which the Wordungmat moiety was named was traditionally of totemic, mythological and ancestral significance to Nyungar people. Armstrong (1836), Interpreter to the Natives, states that one of the earliest origin beliefs was that the first Nyungar arrived on the back of the crow. The indigenous ancestral and totemic significance of this familiar bird has been much overlooked by contemporary non-indigenous sources which tend to denigrate the crow as a nuisance bird (see Appendix 1, Letter to the Editor of the Post Newspaper, ‘Don’t Shoot the Messenger Bird’ by Ken Macintyre).

- Kurannup refers to the ‘place of the dead,’ or ‘place of the ancestors.’ It literally derives its meaning from gorah ‘a long time ago’ (Grey 1840: 47 and Moore 1842: 29) or koora ‘long ago’ (Whitehurst 1992:13) + ‘up’ meaning ‘place of.’

- Mudurup can also be spelt Murdarup, Mudarup or Moodoorup. In Nyungar linguistics ‘u’ and ‘oo’ are usually interchangeable as they denote the same sound (as for example in the name Nyungar or Nyoongar).Grey (1840: 92) and Moore (1842: 57) document mur-dar as ‘a species of fish’ at King George Sound. However, neither identifies it to type. Neill (1846) records murdur as whiting in his comprehensive catalogue of Aboriginal fish names recorded by him at King George Sound (Albany). Hassell (1890’s) records it as mudu and Rae (1913) as muda and murdo – all being variant renditions of the same term.

- The religion of the Nyungar, like other indigenous people throughout Australia, was deeply involved with mythology relating to the Creative Period or Dreaming (Nyitting or Nyettingar). An important aspect of their religious focus involved the restoration and revitalisation of bird, animal, insect and fish populations through ‘increase rituals’ at certain places. Bodney has suggested that fish (whiting) increase ceremonies may have taken place at Mudurup Rocks. Another known fish (mullet) increase site is located at Pelican Point, Nedlands, recorded by Ken Colbung.

- Another piece of anecdotal evidence was collected from my father Don Dobson (personal communication 2000) who recalled that at the height of the depression in the 1930’s many men from the Perth area sustained their families by catching whiting in and around Mudurup Rocks. He said it was a plentiful fish and that the best time to catch them was ‘before the sea breeze came in’. He said ‘most of us used gidgees made from three prongs stuck into a broom handle.’

- Wobbegong (carpet shark) is believed to derive from a New South Wales Aboriginal language where the term is believed to translate as ‘shaggy beard.’ This is presumably a reference to the small weed-like whisker growths around the fish’s mouth. The genus name Orectolobus derives from Greek orectos, meaning ‘stretched out’ and lobos, meaning rounded projection or protuberance, referring to these barbels on its head (see Figure 8). Other common fish names believed to be derived from Australian Aboriginal languages are morwong, mulloway, nannegai, tarwhine, wirrah and barramundi (Sydney Morning Herald 17th January 1953).

- The Fish Habitat Protection Area encompasses the entire Cottesloe Reef System and coastal waters. It stretches along the coastline for approximately 4.4 kilometres from Swanbourne (Grant Street) in the north to Leighton Beach (overhead pedestrian pass) in the south. It extends 800 metres offshore from the high water mark. Within the FHPA area there is a complete ban on spearfishing, boat anchoring, the use of jet skis (except surf life savers) and the collection of marine organisims (crayfishing is permitted in season). Drift fishing and fishing from the shoreline are permitted.

- Moon-do can also be spelt as moondu, mundu, moonda, munder, mundo and moondo, depending on the source consulted. Symmons, Protector of Aborigines (1841: vi) like Grey and Moore records mundo as ‘shark’ but does not identify it to any particular species or type. Dench (in Thieberger and McGregor 1994: 185) lists mundu as tiger shark but does not specify his source. He lists Moore (1884) and Douglas (1976) as his only references but neither of these mentions tiger shark.

- We would suggest two reasons for the non-consumption of shark meat by Nyungar people: (i) the flesh tends to have a strong taste and smell of ammonia and (ii) there is a high degree of danger involved in hunting such large predators with a hand-held spear or gidgigarbel. The blue shark or matchet as it was called at King George Sound (see Neill 1846) was commonly known to “herd” spawning salmon towards shore at the Sound during the indigenous season known as meerteluk (February to April). Teutscher (2012) records blue shark as having a high ammonia content.

- The name Cudgel can also be rendered as Cudgen, Cadgill, Cadjill, Cudgell, Kudjil, Kadjil or Katjil, depending on which historical or contemporary source is consulted. The early Albany Police Court Records refer to Cudgel as Cudgen (cited in the Australian Advertiser 2/5/1892) whereas later police records identify him as Cadgill (cited in the Australian Advertiser 10/8/1892). Cudgen may have been his Aboriginal name or a nickname. It comes very close to kadjin (or kadgin, kadgeine or cachin (Curr 1886) a term which translates as ‘ghost’ or ‘spirit’ (see Symmons 1841: 25 and Moore 1842:38). It is not hard to imagine that Cudgen was a nickname referring to his fleetness of foot and ability to disappear from authority in the blink of an eyelid, or as the Truth (14/5/1904) portrayed him:

- ‘Johnny Cudgell, a notorious Albany blackfellow, was consigned to the local jimbo the other day under remand on a charge of stealing. The lock-up keeper forgot, however, to plug up the keyhole at night, and found next morning that Johnny had crawled through and escaped. Police haven’t seen him since, and are not likely to.’ In newspaper accounts he was commonly referred to as Cudgel. Could this have been a hard-hitting Anglicisation of Cudgen, we wonder? It would seem that Cudgen, who was a clever and literate man, soon adopted his popularised media name Cudgel. He became well known in the newspapers for his many notorious and heroic exploits. One of these sources, the Sunday Times, dramatised him as being one of Western Australia’s most notorious Aboriginal bushrangers who made a mockery of police by escaping from their custody, outsmarting them and leading them in circles around the country. In 1905 while incarcerated at Rottnest Island, Cudgel heroically saved the life of a white prisoner caught in dangerous rocks and surf off the west side of Rottnest. Although he was highly praised by prison authorities, and even the Comptroller-General of Prisons, Mr Oct. Burt, for his bravery, he was refused an award from the Royal Humane Society on the grounds that the Society did not give awards to prisoners (Western Mail 1905).

- Personal communication, R. Bropho 1999.

BIBILOGRAPHY

Appleyard,S.J., Macintyre, K. and B. Dobson 2001 “Protecting ‘Living Water’: involving Western Australian Aboriginal communities in the management of groundwater quality issues“. Paper presented at the International Groundwater Management Conference, University of Sheffield, England. April.

Armstrong, F. 1836 ‘Manners and Habits of the Aborigines of Western Australia, from information collected by Mr F. Armstrong, Interpreter.’ The Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal 29/10/1836, 5/11/1836 and 12/11/1836.

Australian Advertiser 2/5/1892 and 10/8/1892.

Bates, D. ‘A Few Notes on Some South-Western Australian Dialects,’ The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 44 (Jan. – Jun., 1914), pp. 65-82 Published by the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland.

Bates, Daisy 1992 Aboriginal Perth and Bibbulmun Biographies and Legends, P.J. Bridge(ed.), Hesperian Press, Carlisle.

Bindon, P. and R. Chadwick (eds.) 1992 A Nyoongar Wordlist from the South-West of Western Australia. Perth: Western Australian Museum.

Bodney, C. Senior Ballaruk (Nyungar) Elder. Consultations and site visits.

Bropho, R. Senior Nyungar Elder. Consultation.

Brough Smyth, R. 1878 The Aborigines of Victoria. 2 vols. Melbourne and London.

Bunbury, H.W. 1930 ‘Early Days in Western Australia.’ London: Oxford University Press.

Colbung, K. Senior Bibbulmen (Nyungar) Elder. Consultations and site visits.

Curr, E. 1886 The Australian Race: its origins, languages, customs, place of landing in Australia, and the routes by which it spread itself over that continent. 4 vols. Melbourne: Government Printers.

Dench, A. 1994 ‘Nyungar’ in N. Thieberger and W. McGregor Macquarie Aboriginal Words. Macquarie University: Sydney, NSW.

Department of Indigenous Affairs (DIA) (now called Department of Aboriginal Affairs DAA). Perth. Heritage Division. Site Files.

Douglas, Wilfred H. 1976 The Aboriginal Languages of the South-West of Australia 2nd edition, Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra.

Eyre, E.J. 1845 ‘Journals of expeditions of discovery into Central Australia, and overland from Adelaide to King George’s Sound, in the years 1840-1’ Vol. 2. London: T&W Boone.

Green, N. (ed.) 1979 Nyungar -The People: Aboriginal customs in the southwest of Australia. Perth: Creative Research Publishers.

Grey, G. 1840 A Vocabulary of the Dialects of South Western Australia. London: T & W Boone.

Hassell, Ethel (1870’s- 1890’s) ‘Notes and Family Papers’. Battye Library, Perth.

Hassell, Edney n.d. Aboriginal Word List. Department of Land Administration (now Landgate), Perth (typescript). Battye Library.

Humphries, C. Senior Nyungar Elder Consultation and site visit.

Hutchins,B. and Thompson,M. 1983 The Marine and Estuarine Fishes of South-Western Australia. Perth: Western Australian Museum.

Hyndes, Glenn A.; Ian C. Potter (1997). “Age, growth and reproduction of Sillago schomburgkii in south-western Australian, nearshore waters and comparisons of life history styles of a suite of Sillago species”. Environmental Biology of Fishes 49 (4): 435 – 447. doi:10.1023/A:1007357410143.

Macintyre, K. 1973 Unpublished Field Notes.

Macintyre, K. and B. Dobson 1992-2002. Field notes.

Macintyre, K. 2004 Aborigines and the Cottesloe Coast. Paper presented at the Cottesloe Fish Habitat Protection Area Seminar sponsored by Coastcare, May.

Macintyre, K. and B. Dobson 2014 ‘The conveyor of souls in traditional Nyungar culture.’ www.anthropologyfromtheshed.com

Moore, G.F. 1842 A descriptive vocabulary of the language in common use amongst the Aborigines of Western Australia. London: W.M.S. Orr & Co. Paternoster Row.

Moore, G.F. 1884 Diary of Ten Years of an Early Settler in Western Australia. Perth: University of Western Australia Press.

Neill, R. 1845 ‘Catalogue of Reptiles and Fish, Found at King George’s Sound.’ Appendix in E.J. Eyre Journals of expeditions of discovery into Central Australia, and overland from Adelaide to King George’s Sound, in the years 1840-1.

Rae, W.J. 1913 ‘Native Vocabulary’. Department of Land Administration, (Landgate), Perth, typescript.

Sydney Morning Herald, 1953. 17th January, page 9. ‘Folk Names for Fish’ by G.P. Whitely, Curator of Fishes at the Australian Museum.

Symmons,C. 1841 ‘Grammatical Introduction to the study of the Aboriginal language of Western Australia ‘ Appendix to C. Macfaull (ed.) The Western Australian Almanack.

Teutscher,F. 2012 “Sharks (Chondrichthyes)” (On-line) FAO Corporate Document Repository at http:/www.fao.org

Thieberger, N. and W. McGregor 1994 Macquarie Aboriginal Words. Macquarie University, Sydney: The Macquarie Library Pty Ltd.

Town of Cottesloe website ‘Indigenous Culture in Cottesloe’ http://www.cottesloe.wa.gov.au/Community_-About_Cottesloe-Indigenous_Culture.htm

The Grove Library (digital photo collection) http://thegrovelibrary.net/history/community-history-links/ http://trove.nla.gov.au/picture/result?q=mudurup

The Truth newspaper 14/5/1904

The West Australian, 1937 ‘Shadeless Beaches’ by ‘Nautilus.’ Friday 8th January.

Western Australian Underwater Photographic Society (WAUPS) 2001 Photographic Display, Cottesloe Beach, Seadragon Festival, March.

Western Mail 1904 & 1905

Whitehurst, R. 1992 Noongar Dictionary. First Edition. Bunbury, W.A: Noongar Language and Culture Centre.

Whitely, G.P 1953 ‘Folk Names for Fish’ Sydney Morning Herald, 17th January, page 9. G.P. Whitely, Curator of Fishes at the Australian Museum.

APPENDIX 1: Historical Photos of Mudurup Rocks

APPENDIX 2: Don’t Shoot the Messenger Bird

Letter to the Editor, Post Newspaper, by anthropologist Ken Macintyre

The debate about whether to cull the crow population because of their cacophonous calls which disturb the quiet serenity of our Western Suburbs in Perth seems to have overlooked the fact that the crow was here long before we were and is an indelible part of the Aboriginal mythology of the Swan Coastal Plain. The crow or Australian Raven (Corvus coronoides) is an icon bird in Nyungar mythology. Throughout Perth and the southwest, this bird, known by Nyungars as warrdong (sometimes spelt warding, wording, wordung, wordang) was one of the major totemic symbols and ancestral spirits of the Southwest Aboriginal moiety system. The black crow moiety was known as Wordungmat, while its counterpart, the white cockatoo moiety was called Manichmat (derived from manich, manyt or munitch meaning white cockatoo).

In traditional Nyungar mythology the warrdung (crow) typically assumed the role of a wise old man, a cunning trickster or a malicious “bulya man” or sorcerer who had great powers over humans. In Aboriginal mythology it was not uncommon for sorcerers to metamorphise into crows and to travel great distances in such a guise to seek out their unsuspecting victims. There was no escaping the crow man.

When birds, such as the crow, came into close contact with humans and acted in an unbird-like manner, they were not regarded as birds but rather as spirits from another world conveying messages to humans. Nyungar mythology contains a panoply of messenger birds, some of which convey good news, others bad news. Indigenous people were very conscious of birds and their actions, as were the ancients of Greece and Rome with their auguries.

In Nyungar culture the crow was also an important indicator bird, especially on the coast, where its presence in large numbers and its raucous calls signalled the presence of large schools of fish, such as mullet and salmon, especially along coastal embayments such as at Mudurup Rocks. One elderly Aboriginal informant explained that the “run” of the warrdung extended from Rottnest Island to Mudurup “place of the yellow-finned whiting”), which is now Cottesloe. He said that these birds were weather indicators, heralding the coming of stormy weather. The crows would announce to the black cockatoos that wet weather was on the horizon, then the black cockatoos would announce it to all the other animals and insects. For signalling the arrival of fish the warrdung were rewarded by an abundance of fish entrails and waste.

A more contemporary Nyungar mythology describes how an Aboriginal prisoner from Rottnest Island known as Kudjil (sometimes spelt Cudgel or Cudjil) transformed himself into a crow and escaped to the mainland. He is said to have landed at Cottesloe or Swanbourne Beach before joining his people who were camped in the sand hills just inland at Swanbourne. Although there is no documented evidence of Kudjil escaping from Rottnest Island, the descendants of the people who camped at Swanbourne in the early part of the 20th century were (and still are) convinced that Kudjil’s spirit escaped and visited his people in the guise of a crow. This mythology is well known by many of the older Aboriginal people who camped there up until the 1950’s.

This is only a small and localised part of the oral tradition relating to the warrdung as an icon bird in Nyungar mythology in south-western Australia. With regards to the culling of the crows an Aboriginal Elder recently told me ‘the trouble with you white-fellas is that you have no idea about the balance of Mother Nature. When something gets out of balance you don’t fix it by shooting it. You don’t shoot the messenger bird. You try to understand what it’s telling you.’

Maybe what the crows are telling us is that their exploding population is the result of their adaptation to our very generous society which provides them with an abundance of waste in our backyards, rubbish dumps and beaches. Maybe they have a message for us.